Monsters, Witches, and Michael Jackson’s Ghosts

Willa Stillwater

“It’s right that I be contemplated

After having been stared at”

Introduction

Wade Robson, a witness for the defense in the 2005 trial of Michael Jackson, recently recanted his sworn testimony that Jackson never molested him—testimony he steadfastly affirmed again and again, under oath, throughout vigorous cross-examination. However, he now says he was molested, and he and his lawyer, Henry Gradstein, have filed a creditor’s claim against the Jackson Estate seeking financial damages. In a prepared statement quoted May 9, 2013, by the New York Daily News and others, Gradstein told the press, “Michael Jackson was a monster, and in their hearts every normal person knows it.” In other words, Gradstein suggests “normal” people should follow their instincts and assume Jackson was guilty, before any evidence has been presented or considered, because Jackson was clearly not one of us. He was not “normal.” He was, in Gradstein’s words, “a monster.”

In the 1990s, Jackson found himself in a similar situation: the father of a 13-year-old boy claimed Jackson had molested his son. Jackson responded with a musical film, Michael Jackson’s Ghosts, in which a Maestro is accused of corrupting the minds of village children. However, it soon becomes clear the Maestro’s real crime is that he’s so unnervingly different from the other residents of Normal Valley—a village populated by “Nice Regular People,” according to a sign on the edge of town. The town Mayor repeatedly emphasizes this difference when confronting the Maestro and stirring the villagers against him: “He’s a weirdo. There’s no place in this town for weirdos.” “We have a nice normal town, normal people, normal kids. We don’t need freaks like you.” “You’re weird, you’re strange, and I don’t like you. You’re scaring these kids, living up here all alone.” And “Back to the circus, you freak” (Jackson 1997b). Motivated by anger and fear of his difference, the villagers try to drive the Maestro from his home. However, he responds in a very surprising way—a way that diffuses the villagers’ intense emotions, alters their perceptions, and ultimately leads to reconciliation between the villagers and the Maestro.

Ghosts can therefore be interpreted as Jackson’s imaginative reenactment and engagement with the scandal that had engulfed him off screen—specifically, with the cultural, emotional, and psychological dynamics of the accusations and the public outrage that followed. Viewed in this way, Ghosts has the potential to profoundly influence how we perceive and respond to Jackson himself, both as a “Maestro” accused of corrupting a child and as a fellow human ridiculed and feared because he was seen as suspiciously and irreconcilably different.

However, Ghosts accomplishes much more than that. It isn’t just a work of art, but a work about art—about art’s ability to capture our worst emotions, challenge our biased perceptions, and then alter those emotions and perceptions. Drawing on his own case history as a guide, Jackson uses Ghosts to map out an artistic approach for attacking cultural biases not only in an intellectual way but at a deep psychological level—in a place of sensation and affect, a place resistant to evidence and reason, a place where our most primal fears, prejudices, and desires hold sway. Significantly, this is also the place where hysteria arises.

Just as importantly, I believe Ghosts and one of its featured songs, “Is It Scary,” point to an entirely new kind of art—a new genre of art—distinct in form and scope from anything we’ve ever seen before. Through this new kind of art, Jackson captured the cultural narratives that were being imposed on him—narratives of race, of gender, of sexuality, of criminality, of celebrity and monstrous excess—inflated them to grotesque proportions, and then reflected those narratives back at us, forcing us to confront and grapple with them, and maybe reconsider them. This new genre is mediated through the tabloids and celebrity television shows and even the mainstream press, and it includes the many “eccentric oddities” (to borrow a phrase from “Is It Scary”) that came to define Jackson in the public mind. However, his greatest achievement in this new genre is his constantly shifting face, or rather our constantly shifting perceptions of his face since the physical structure of his face changed very little. His face is a work of art so revolutionary we don’t yet even recognize it as art, though it has deeply troubled and passionately engaged us for decades—as powerful works of art often do. I believe it has the potential to transform not only how we think about art but how we think about ourselves: how we define identity, how we perceive and categorize ourselves and others, and how we experience the differences that divide us. However, to fully understand this new genre, along with Ghosts and all it accomplishes, we first need to look at the scandal that inspired it, as well as an important antecedent that occurred more than 300 years ago.

Monsters

In 1993, Michael Jackson was accused of molesting a young boy, Jordan Chandler. The case against him is problematic at best. In early 1993, the boy’s father, Evan Chandler, began making vague threats against his ex-wife, June Wong Chandler, and hinting at a scheme against Jackson as well. Jordan’s stepfather, David Schwartz, became so alarmed by his speculative talk that he began recording their phone conversations. Chandler later sued Schwartz for taping him without his knowledge, Schwartz countersued, and in the course of those lawsuits a transcript of their conversations was filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court. That transcript reveals a complex brew of emotions, including resentment, anger, jealousy, and greed. In those conversations, Chandler tells Schwartz he has paid people to carry out a “plan that isn’t just mine” (Transcript 220) and boasts, “If I go through with this, I win big time. There’s no way that I lose. I’ve checked that inside out” (133).[2]

Importantly, Chandler’s primary motivation seems to be intense anger against his ex-wife and Jackson for ignoring him, rather than concern for his son’s wellbeing. As he tells Schwartz, “I had a good communication with Michael. We were friends, you know. I liked him. I respected him and everything else for what he is. There was no reason why he had to stop calling me” (168). However, if his “plan” succeeds, he will “get their attention” and more:

Chandler: I will get everything I want, and they will be totally—they will be destroyed forever. They will be destroyed. June is gonna lose Jordy. She will have no right to ever see him again.… Michael, the career will be over.

Schwartz: Does that help Jordy?

Chandler: Michael’s career will be over.

Schwartz: And does that help Jordy?

Chandler: It’s irrelevant to me. (134)

So instead of focusing on what’s best for his son, Chandler repeatedly expresses bitter resentment toward those he feels have ignored and excluded him, including Jordan to some degree. As Chandler tells Schwartz, “June, Jordy, and Michael have forced me to take it to the extreme to get their attention. How pitiful, pitifuckingful they are to have done that” (207).

Driven by anger as well as greed, Chandler seems bent on taking his revenge if his demands are not met, as he tells Schwartz:

This attorney I found—I mean, I interviewed several, and I picked the nastiest son of a bitch I could find, and all he wants to do is get this out in the public as fast as he can, as big as he can, and humiliate as many people as he can.… I mean, it could be a massacre if I don’t get what I want. But I do believe this person will get what he wants.… He is nasty, he is mean, he is very smart, and he’s hungry for the publicity. (27)

So as Chandler predicts, “it could be a massacre if I don’t get what I want.” What he wants is attention and $20 million, and helping his son is, in his words, “irrelevant to me.”

Eight days after this conversation, Chandler, who was a dentist, took his son to his dental office. He pulled one of Jordan’s baby teeth and then aggressively questioned the boy about his relationship with Jackson—a very odd place and time to raise such a sensitive subject. According to Chandler’s written chronology, which he gave to police, his interrogation of his son was both manipulative and coercive. First, he begins the conversation by lying to his son. As he writes in his chronology, he “falsely told” his son “I had bugged his bedroom” when he had not, and “I knew everything” when he did not (Dimond 2005, 60). He then fabricates a story that includes explicit sexual acts and tells the boy he knows that he and Jackson have done these things. Specifically, he tells his son, “I know about the kissing and the jerking off and the blow jobs.” Importantly, these are precisely the acts the boy will describe when he goes to see a psychiatrist a month later kissing, masturbation, oral sex. Chandler asks his son to confirm this story of sexual misconduct, telling him that “I knew everything anyway and that I just wanted to hear it from him.” He then threatens to destroy Jackson’s career if the boy doesn’t answer his questions the right way, saying that if he doesn’t tell him what he expects to hear, “then I’m going to take him (Jackson) down” (60, parentheses his). However, he promises not to “hurt Michael” if he complies. Based on Chandler’s own written chronology, he clearly conducted the questioning in a very deceptive and coercive way, asking leading questions and threatening to harm Jackson if his questions were not answered correctly.

However, the case is complicated still further by the presence of a third person in Chandler’s office that day: Mark Torbiner, an anesthesiologist who had been asked to leave his previous position because of ethics violations and now made a living providing anesthesia for hire, often in private homes (Fischer 1994, 221). Chandler wrote in his chronology that he waited until the sedation wore off before questioning his son: “When Jordie came out of the sedation I asked him to tell me about Michael and him” (Dimond 2005, 60).[3] However, in a KCBS-TV report broadcast May 3, 1994, Chandler says the allegations were made while his son was still sedated. This directly contradicts the written chronology he gave to police. If Chandler’s statements to KCBS-TV are true, it is very troubling that Jordan first agreed to the allegations while under the influence of some unknown drug, especially given the way his father conducted the questioning: with lies and threats and the suggestion of specific sexual acts.[4]

Despite such dubious evidence, Santa Barbara District Attorney Tom Sneddon aggressively pursued the case against Jackson. At his direction, a humiliating strip search was conducted on December 20, 1993, that focused on examining, photographing, and videotaping the most intimate areas of Jackson’s body. The ostensible purpose of the strip search was to see if Jordan’s description of Jackson’s body was correct. Jackson’s former wife, Lisa Marie Presley, later said it was not correct. In an interview broadcast June 14, 1995, on ABC’s PrimeTime Live, Presley told Diane Sawyer, “There was nothing that concurred. There was nothing.” Additionally, two independent grand juries—in Santa Barbara County and Los Angeles County—reviewed the evidence against Jackson, “including the description of Jackson’s genitalia given by Jordie that was laid out next to the photographs of Michael’s lower body” (Sullivan 2012, 266), and both juries refused to return an indictment. As Randall Sullivan explains in Untouchable: The Strange Life and Tragic Death of Michael Jackson, this is significant:

Grand juries are generally a formality in California; nearly all such deliberations end in indictments. Only prosecutors can present evidence, and they are required to demonstrate no more than a “reasonable likelihood” that a crime has been committed. Yet in the summer of 1994, both grand juries refused to indict Michael Jackson. “There was no real evidence,” a police officer involved in the investigation admitted to the Los Angeles Times. (266)

Taken together, the judgment of both grand juries along with the statements by Presley and the officer who spoke to the Times seem to corroborate an earlier Reuters report picked up by USA Today on January 28, 1994, only a few weeks after the police conducted the strip search: “An unidentified source told Reuters news service Thursday that photos of Michael Jackson’s genitalia do not match descriptions given by the boy who accused the singer of sexual misconduct.”

However, a corollary outcome of the strip search was that extremely graphic photographs and videotape of Jackson’s naked body were now in the hands of the police. Those images could be made public during a trial, a situation that would be mortifying for anyone but especially for someone as subject to public scrutiny as Michael Jackson. In addition, copies of those photographs and videotape could be turned over to Chandler and his lawyer, Larry Feldman, as they prepared for the trial. Those images would be worth millions from the tabloids or porn outlets, and Chandler was a man determined to obtain millions. He also wanted to “humiliate” as many people as possible, and those graphic images of Jackson’s naked body would give him the tools he needed to thoroughly humiliate Jackson. As Chandler told Schwartz, “This man is going to be humiliated beyond belief.… He will not believe what’s going to happen to him. Beyond his worst nightmares” (Transcript 201). Those photographs—or even the threat of those photographs—could also be used to pressure Jackson to negotiate a settlement. Chandler’s brother, Ray, attended many of the meetings with Feldman, and he describes the situation this way: “The DA might soon have pictures of Michael’s cajones, but Larry Feldman now held them firmly in his grasp. And it was time to put the squeeze on” (Chandler 2004, 209).

Jackson agreed to settle the civil case a few days after the strip search and, as Sullivan reports, preventing the release of those photographs was the central issue during negotiations between Feldman and Jackson’s lawyers, Johnnie Cochran and Howard Weitzman:

Cochran and Weitzman regarded the photographs of Michael Jackson’s genitalia as “the purple gorilla sitting in the room,” recalled [Cochran associate] Carl Douglas, and were desperate to keep them out of Larry Feldman’s hands. Fully aware of this, Feldman negotiated ferociously. “The numbers being discussed seemed fantastic,” remembered Douglas, who believed that the turning point of the settlement conference came when one of the three retired judges [mediating the negotiations] observed that, “It’s not about how much this case is worth. It’s about how much it’s worth to Michael Jackson.” (265)

Jackson ultimately decided it was worth millions to him to prevent the police photographs of his naked body from being turned over to a man determined to humiliate him “[b]eyond his worst nightmares,” but he insisted the settlement be structured so most of the money was held in trust for Jordan until he came of age. Evan Chandler reportedly received $1.5 million, and Jordan an estimated $15 million. Jordan would later use this money to break free from his abusive father. (Jordan emancipated himself while still a minor and later requested a restraining order against his father. At the hearing, he said his father had struck him in the back of the head with a barbell, sprayed him in the face with mace, and tried to strangle him. According to court documents, a judge in the case noted that Chandler’s actions could have seriously injured his son, or even caused his death [Jordan 2006].) Importantly, Jackson could have prevented the scandal by settling the case six months earlier before it became public, but he adamantly refused and continued refusing for months. However, he abruptly changed his mind and agreed to settle the case within days of the strip search.

As soon as settlement of the case was finalized, Jackson had his lawyers quietly petition the court to obtain the photographs and videotape of the strip search. They were denied. However, those images continued to weigh on his mind apparently because 12 years later, as soon as the 2005 trial was over, he once again had his lawyers petition the court to obtain them. Again they were denied. Unless they have been destroyed since his death, those photographs and videotape remain in legal custody (Dimond 2005, 321).

Settling the civil case was interpreted by many as an admission of guilt, and this only fueled the firestorm of hysteria surrounding the case—a firestorm stoked ever higher by a global media eager to emphasize and exaggerate the most lurid aspects of the story, whether true or not. For example, the television tabloid Hard Copy paid one of Jackson’s maids, Blanca Francia, $20,000 to appear on the show and say she had seen Jackson naked with young boys in the shower and Jacuzzi. However, a month later while under oath giving a deposition about what exactly she had seen, she contradicts this: she never saw Jackson in the shower with anyone, and he always wore swim trunks in the Jacuzzi (Fischer 1994, 267; Halperin 2009, 64-71).

Francia also told Hard Copy that Jackson may have molested her 12-year-old son, Jason (Halperin 2009, 64-65). He is the second boy Jackson is accused of sexually abusing. Officers investigating the Chandler case questioned the boy both before and after the show aired, and initially he told them Jackson had done nothing wrong. However, the investigators didn’t accept his answer and pressured the boy to allege abuse, asking leading questions such as whether Jackson may have molested him while tickling him. In a June 13, 2010, article in The Huffington Post, Charles Thomson states that, according to transcripts of the interviews,

[Jason] had originally insisted that he'd never been molested. Transcripts also showed that he only said he was molested after police officers repeatedly overstepped the mark during interviews. Officers repeatedly referred to Jackson as a “molester.” On one occasion they told the boy that Jackson was molesting Macauley Culkin as they spoke, claiming that the only way they could rescue Culkin was if Francia told them he’d been sexually abused by the star.

(Culkin has consistently denied speculation that Jackson abused him, including under oath during the 2005 trial.) Jason finally agreed to the accusations, saying that on three occasions while he and Jackson were both fully clothed, Jackson touched him inappropriately while tickling him. Thomson reports that, according to the transcripts, Jason said the officers questioning him “made me come up with stuff. They kept pushing. I wanted to hit them in the head.” The Francias received a $2.4 million settlement from Jackson’s insurance company.

Ten years later, Jackson was accused of molesting a third boy, Gavin Arvizo, a cancer patient who had requested to meet Adam Sandler, Chris Tucker, and Michael Jackson. They all agreed. Gavin later appeared in a documentary with Jackson and said, after prompting by the filmmaker, “There was one night when I asked him if I could stay in his bedroom” (Living 2003). Gavin and Jackson went on to say that Gavin slept in Jackson’s bed that night while Jackson slept on blankets on the floor. The filmmaker, Martin Bashir, then questioned Jackson about his motives, saying, “But Michael, you’re a 44-year-old man now. What do you get out of this?” Jackson replied,

I’ve said it many times, my greatest inspiration comes from kids. Every song I write, every dance I do, all the poetry I write—it’s all inspired from that level of innocence, that consciousness of purity. And children have that. I see God in the face of children. And man, I just love being around that all the time.

When the documentary aired on February 3 and 6, 2003, in the UK and US, respectively, many viewers found Jackson’s answer unsettling and felt the entire situation was inappropriate. This scene also raised suspicions of sexual abuse and triggered investigations by the Los Angeles Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), the Los Angeles Police Department, and the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Department. The Arvizos later accused Jackson of molesting Gavin, and this time the case went to trial.

However, as with the Chandler and Francia allegations, the Arvizo case is deeply problematic. For example, instead of reporting the alleged abuse to the police officers investigating the case, or to a school counselor or therapist, the Arvizos consulted with and retained Larry Feldman, the lawyer who negotiated the Chandler settlement. More significantly, according to the dates recorded in the indictment and read aloud by District Attorney Sneddon in his opening statement on the first day of the trial, the molestation allegedly occurred between February 20 and March 12, 2003 (Reporter’s Transcript 2005, 12-13). If those dates are correct, that means the abuse occurred after the Bashir documentary aired, after the scandal erupted, and after DCFS and two law enforcement departments began their investigations. In other words, according to the prosecutor’s timeline, Jackson was innocent of any wrongdoing when the scandal broke, and then—while under intense scrutiny by DCFS, the police, the press, and the public—he committed the crime he was already under investigation for committing. That strains credulity. Prosecutors also claimed that a conspiracy to cover up the crime began before the crime allegedly happened, as Tom Mesereau, the lead attorney for the defense, mentioned in his closing arguments:

According to the prosecution, this criminal conspiracy is beginning on February 1st, 19 days before the alleged molestation. Put all this together, what does it say to you about the dates the so-called molestation occurred? It’s absurd. It’s unrealistic. And it makes no sense. Because the whole case makes no sense. (Reporter’s Transcript 2005, 12874)

After considering this convoluted chronology as well as numerous other highly questionable aspects of the case, the twelve members of the jury unanimously found Jackson not guilty of all charges. The public might have reached the same conclusion if the basic facts of the case had been reported by the press.

Of course, the flood of sensationalized stories received far more attention than the evidence refuting them, and Jackson went from being one of the most popular public figures in the world to an object of scorn and even hatred. As he himself describes, he became a “monster” in the public mind, and many of his later songs can be interpreted as engaging with and challenging this monstrous public image. In “Threatened,” the protagonist calls himself “your worst nightmare,” an embodiment of “the dark thoughts in your head,” and “a monster, the worst thing to fear” (Jackson 2001). In “Is It Scary,” he asks, “Am I the beast you visualized?” (Jackson 1997a). In “Breaking News,” he asks, “Who is this bogeyman you’re thinking of?” (Jackson 2010). And in “Monster,” Jackson seems to echo public perceptions of himself with the repeated refrain:

Monster

He’s a monster

He’s an animal (Jackson 2010)

By the time the Arvizo scandal broke in early 2003, the hysteria had reached such a fever pitch that Vanity Fair ran an article accusing him of voodoo, with a chanting witchdoctor allegedly conducting ritual sacrifices of cattle, poultry, and “small animals” on his behalf.[5] In such an emotionally charged atmosphere, it became nearly impossible to separate truth from fear, fantasy, and conjecture. Jackson would carry the stigma of pedophilia for the rest of his life.

Looking back, this long series of events can all be traced to that moment in 1993 when Chandler said, “If I go through with this, I win big time. There’s no way that I lose…. I will get everything I want, and they will be totally—they will be destroyed forever.… Michael’s career will be over” (Transcript 133-134). In many ways, Chandler’s predictions came true. Once he set his “plan” in motion, it implanted the image of Jackson as a pedophile in the minds of the police, the press, and the public, and it can be argued that the cascade of events that followed are all the direct result of that artificially produced mental image. For example, I don’t believe the officers questioning Jason Francia would have pressured him to allege abuse—or at least, not so persistently—if Chandler’s accusations hadn’t already convinced them that Jackson was a child molester. I don’t believe the Bashir documentary would have caused such an outcry if Chandler’s accusations hadn’t already embedded the image of Jackson as a pedophile in the popular imagination. And I don’t believe a case as flawed as the Arvizo case ever would have gone to trial if District Attorney Sneddon hadn’t already spent 10 years and millions of dollars trying to convict Jackson of sex crimes against children based on Chandler’s statements. This is one way mass hysteria manifests itself: when one sensational accusation sets off a chain reaction of other sensational accusations.[6]

But why did the Chandler case play out the way it did? Why did the police believe Chandler and disbelieve Jackson, despite the contradictions in Chandler’s statements and numerous other red flags? Why did the press exaggerate and even invent “evidence” against Jackson while suppressing evidence exonerating him? For example, few media outlets acknowledged that Jordan first agreed to the allegations either during or immediately after sedation, and after his father pulled out one of his teeth—a coercive situation if ever there was one. Few mentioned that Chandler threatened to destroy Jackson’s career if Jordan didn’t answer his questions the way he wanted. And few reported that two independent grand juries reviewed the evidence against Jackson and refused to indict him. Yet these are all undisputed and crucially important facts in this case since they cast significant doubt on Jordan’s testimony, and his testimony appears to be the only evidence against Jackson.

Although it may seem irrelevant at first, perhaps one reason the police and the press were so quick to believe the allegations against Jackson was the changing pigmentation of his skin. In The White Afro-American Body: A Cultural and Literary Exploration, Charles D. Martin raises the possibility that Jackson’s skin marked his body as a site of sin and corruption before he ever met the Chandlers, before he was ever accused of anything. Martin traces the public exhibition of black bodies with white skin, particularly the bodies of those suffering from vitiligo or albinoism, from slavery through segregation to the present day, and he provides important historical contexts for understanding Jackson’s body both as spectacle and as alleged crime scene. Martin claims that “white Negro” bodies have fascinated and threatened white audiences for more than two centuries by challenging notions of racial essentialism and purity. As a corollary effect, the image of a black body with white skin also arouses confused notions of miscegenation, contamination, and corruption that apparently survive even today:

[T]he spectacle of vitiligo still bears the taint of fraud and traitorous racial conversion. The folk wisdom surrounding the disorder associates the appearance of whiteness on dark skin with sexual escapades across the color line. (166)

Given this historical context, Martin suggests that Jackson’s “white-and-black skin” itself became “primary evidence of his madness, his perversity, his crimes” (175), an irrational prejudice that perhaps gained additional potency because he was accused of a sex crime “across the color line.”

John Nguyet Erni provides a broader view, suggesting that the Chandler allegations were quick to gain currency not only because of Jackson’s shifting skin color but because of his ambiguous figuring of identity more generally, both on and off screen—an ambiguity that’s both captivating and profoundly unsettling. As Erni notes, in Black or White we see Jackson transform into a black panther and then back to human, but a somewhat different human than he was before—an angry human, “howling and dancing in violent rage” (162). In Thriller he portrays a shy teenager out on a date who transforms into a werewolf and then “returns as a teenage lover,” but a teenage lover with a difference—“with the morphologically transformed eyes of a monster.” Jackson transforms into the Other and back again repeatedly in his short films, but as Erni points out, in general the “return” to human form is not quite “a return to the ‘original.’” Rather, it is a return that still carries the traces of Otherness, “a gesture of a ‘return’ signifying metamorphosis.”

These recurring transformations hold both a promise and a threat. Jackson’s forays into Otherness open the possibility of “a creative re-imagination of identity” (Erni 1998, 163)—an ethos of possibility and change that proved very appealing to his fans around the world, especially those who were themselves marked as Other. (As Julian Vigo notes, “While making a film on the public mourning of Jackson … I was rather surprised how many of Jackson’s fans identified with him due to their own marginalization due to disability, illness, sexuality and ethnic identity” [32].) However, it also tapped a deep anxiety toward the ambiguous, the unfixed, the uncanny, and the unknown that the mainstream and even alternative media seemed to find intolerable—hence the extreme condemnation of Jackson and his characterization as “Wacko Jacko.” As Erni suggests, perhaps this discomfort with Jackson’s ambiguous identity helps explain the “escalating trend of demonization of Jackson by the media and the public” (159) before the Chandler scandal broke, which then morphed into “a tale of perversion that fits and refuels the media’s ongoing production and consumption of the queer stardom of a ‘man-child’” (160) once the allegations became public.

A third factor in public reactions to the Chandler case was an understandable sympathy for the alleged victim, which was heightened by a climate of increased sensitivity toward abuse victims following a rise in public awareness in the 1970s and 80s and a series of highly publicized and highly controversial daycare sexual abuse scandals in the 1980s and early 1990s. (The McMartin Preschool trial in Los Angeles County, which ended in 1990, still stands as the longest, most expensive criminal trial in US history, and one of the most sensational. The seven defendants were accused of Satanic ritual abuse as well as sex crimes against young children.) Because victims of sexual abuse too often have been doubted and shamed into silence, there is now a deep reluctance to question accusations of childhood sexual abuse, regardless of the circumstances under which they are made. This tendency to refrain from asking legitimate questions about the validity of abuse allegations—or, even further, to assume all such allegations must contain some kernel of truth—no doubt played a role in public perceptions of the Chandler case.

However, according to Tom Mesereau, Jordan Chandler himself has quietly denied his own statements, saying his parents forced him to make false accusations against Jackson. Mesereau spoke at Harvard Law School on November 29, 2005, as part of a lecture series on race and justice. During a question-and-answer session after his presentation, he was asked about the Chandler case, which was brought in as evidence of “prior bad acts” during the 2005 trial. In his answer, he said Jordan had told acquaintances the allegations are untrue:

I had witnesses who were going to come in and say he told them it never happened, and that he would never talk to his parents again for what they made him say.

While Jordan has not made a public statement disavowing the allegations, according to Mesereau these witnesses were willing to appear in court and testify under oath that he had made such statements in private.

Unfortunately, Mesereau’s comments received very little attention in the press. By contrast, sensationalized stories of Jackson’s private life—especially stories that reinforce the monstrous “Wacko Jacko” image of him perpetuated in the tabloids and even the mainstream media—routinely receive inordinate attention. Clearly, media coverage of the scandals, and the public reaction that’s followed, has not been driven by a careful review of the evidence. While some of this bias may be attributed to sensitivity toward the alleged victims, that doesn’t explain why the basic facts of the 1993 allegations and 2005 trial have been so misrepresented, or why Jackson has been so thoroughly “demonized” as Erni characterizes it, or why the allegations still arouse such intense emotions even now, more than 20 years after he was first accused and five years after his death. What drives this impulse to portray Michael Jackson as a “monster”? And what accounts for the tendency toward mass hysteria in this case? Jackson asked questions like these again and again in his later work, and his supporters have wrestled with them since 1993. But perhaps some answers may be found much further back, in another case of mass hysteria with deep roots in our nation’s history and psyche—a case that illuminates our centuries-long anxiety about race and difference, as well as our conflicted feelings about children and sexuality.

Witches

In 1692, a slave named Tituba was accused of practicing witchcraft in Salem Village, Massachusetts. Nine-year-old Betty Parris, the daughter of Tituba’s owner, Rev. Samuel Parris, had been experiencing unusual physical symptoms since December 1691, with sharp pains and uncontrollable spasms contorting her small body. Within a few weeks, five other girls began exhibiting similar symptoms. Suspicions of witchcraft spread quickly, as they often did in those days. However, something different happened in Salem Village, and those fairly commonplace fears erupted into mass hysteria. By the time the Salem witch trials ended in September 1692, nearly 200 people had been accused of witchcraft, and 20 of them had been executed.

A critical event in the story of the Salem witch trials occurred on February 25, 1692, when Mary Sibley, a concerned neighbor and member of Rev. Parris’ church, approached Tituba and her husband John and asked them to create a witchcake to identify the source of the devilment. Using a witchcake to ferret out a witch was a fairly common practice of European origin, as Elaine G. Breslaw explains in Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem, but ironically Sibley may have approached Tituba with her request because she and her husband were American Indian and “because sympathetic magic was so closely identified with Indians” in the Puritan imagination (97). As Breslaw notes, “It was not necessary that Tituba and John have personal reputations as cunning folk, only that they fit the stereotype of effective witches” (97). In fact, there is no evidence that Tituba or John ever engaged in occult practices before asked to do so by Sibley, and there is considerable circumstantial evidence to suggest they didn’t.

Interestingly, Tituba and John’s race and ethnicity have evolved significantly since the time of the trials. In contemporary reports they were repeatedly and unequivocally identified as “Indian.” However, in retelling the story, authors gradually shifted them toward an African ancestry. In “Giles Corey of the Salem Farms,” written 175 years after the trials, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow characterizes Tituba as the daughter of an Indian mother and an “all black” father who taught her Obeah magic (113), and by the time Arthur Miller wrote The Crucible in 1952, another 85 years after Longfellow, Tituba had become a “Negro slave” (7) who gave the girls chicken blood to drink, encouraged them to dance nakedly in the woods, and was “known to have indulged in sorceries” with them (33). Chadwick Hansen traces the progression of Tituba’s race and the type of witchcraft attributed to her in “The Metamorphosis of Tituba, or Why American Intellectuals Can’t Tell a Native Witch from a Negro”:

Over the years the magic Tituba practiced has been changed by historians and dramatists from English, to Native, to African. More startlingly, her own race has been changed from Native, to half-Native and half-Negro, to Negro.... There is no evidence to support these changes, but there is an instructive lesson in American historiography to be read in them. (3)

As Hansen notes, by the 1950s, “Tituba’s magic is blacker as well as her race” (10) and she is depicted as adept in voodoo, though there is no evidence of that and she was not accused of voodoo practices at the time.

After the witchcake incident, the girls’ symptoms worsened and spread to other girls and several women, and the witchhunt began in earnest. Rev. Parris beat Tituba until she confessed to making the witchcake but not engaging in witchcraft, then turned her over to local authorities who began an inquiry. Tituba was questioned over a period of five days and, according to Breslaw, at some point was subjected to a “minute and humiliating” examination of her nude body, “including the genital area, for signs of a ‘witches’ teat’ or some mark from which, according to legend, the Devil and his familiars suckled their converts” (131). When this examination failed to provide the evidence they wanted, she was examined at least once more for verification. Breslaw notes that this kind of bodily scrutiny also derived from a European conception of witchcraft: “Such marks had been used traditionally both in England and in New England as empirical evidence of a diabolical association.”

Finally Tituba was brought before the magistrates on “Suspition of Witchcraft” (Warrant 2004, 78) and her testimony electrified the crowd who packed the public house where the inquiry was held. She confessed, and in spectacular fashion. When she had denied Rev. Parris’ accusations of communing with the Devil, he had interpreted her denials as defiance and punished her even more harshly. The magistrates had subjected her to at least two demeaning examinations and seemed as intent as Rev. Parris on either gaining a confession or obtaining some other proof of guilt. Clearly, denying the accusations wouldn’t protect her. So for complex reasons that are far from clear, Tituba confessed to the crime of witchcraft.

However, she did more than that. She was an accomplished storyteller who enjoyed telling stories to Betty and other girls, and she captivated her audience with her testimony—a talent that perhaps saved her from the gallows, as Breslaw explains:

Tituba the storyteller prolonged her life in 1692 through an imaginative ability to weave and embellish imaginative tales. In the process of confessing to fantastic experiences, she created a new idiom of resistance against abusive treatment and inadvertently led the way for other innocents accused of the terrible crime of witchcraft. Her resistance, a calculated manipulation of Puritan fears, was intimately related to her ethnic heritages. Puritans were predisposed to believe that Indians willingly participated in Devil worship. That perception of Indians as supporters of the Devil encouraged Tituba to fuel their fantasies of a diabolical plot. As she hesitantly capitalized on Puritan assumptions regarding Satanism, Tituba drew on the memories of her past life for the wondrous details of a story so frightening in its implications that she had to be kept alive as a witness. (xx)

So while Tituba capitulated to her accusers’ demands and confessed to a crime she did not commit, Breslaw suggests that her capitulation was itself a mode of resistance—“a new idiom of resistance”—that captured the villagers’ fears, amplified them, and then reflected those inflated fears back at her spellbound audience. In other words, if the residents of Salem Village were going to abuse and molest her until she told them a witch’s tale, then she’d give them a witch’s tale—a tale “so frightening in its implications” it would scorch their eyebrows and make them hesitant to abuse her again.

So what can the story of Tituba teach us about Michael Jackson? There are many obvious correlations to the Jackson case, from the predisposition to believe her guilty, to the strip search and genital examination by authorities, to the insinuation of voodoo practices by later chroniclers of her story. But there are other, less obvious parallels that in many ways are even more significant, such as her skill as an artist and her forging of “a new idiom of resistance.” These elements of Tituba’s story—particularly, her ability to captivate her audience and occupy their imaginations—are true of Jackson as well, and they have the potential to transform not only how we perceive him, both as a person and an artist, but how we define and conceptualize art itself, as Jackson himself demonstrates in Ghosts.

Ghosts

In 1997, Jackson responded to the climate of hysteria that had engulfed him with the 38-minute short film, Michael Jackson’s Ghosts. The main character is an artist, a “Maestro” as he’s listed in the credits, who likes to tell children stories—just like Tituba. He’s also racially and ethnically ambiguous and perceived as uncomfortably different by his neighbors—again like Tituba, especially the figure of Tituba that has come down to us through the centuries. And as with Tituba, the threat of this ambiguous figure—a figure culturally marked as Other—corrupting the minds of white children ignites mass hysteria. (The Maestro also tells stories to a black child, but he’s not in trouble for that. As the film makes clear, he’s come under attack for exposing two white boys to ghost stories.)

The story opens with a mob of frightened, angry villagers invading the Maestro’s home with torches in hand, intent on driving him out of town. However, the Maestro responds in an unexpected way: ten times he disguises, distorts, or destroys the appearance of his face, and then reveals it’s all just an illusion. (Interestingly, three times he appears without a nose, twice with only a partial nose, and once his nose crumbles off in front of us.) This startling response performs several important functions. First, it shocks the villagers, disrupting the mob mentality that’s gripped them and diffusing their attack. Secondly, it captures the villagers’ free-floating fears, gives those fears a locus, and creates a fairly harmless channel for venting those unruly emotions, thereby functioning in complex ways to provide a measure of catharsis. Finally, it allows the Maestro to gain some control over the situation so he can then use his art to alter the villagers’ response, transforming not only their fear of him but their fear of difference more generally. (The loss of his nose, specifically, also addresses the police and public obsession with Jackson’s sexuality and anatomy since, as Mikhail Bakhtin tells us, “the grotesque image of the nose … always symbolizes the phallus” [316].)

Remarkably, Jackson seems to have used a similar strategy off screen as well. In the late 1990s especially, the tabloid and mainstream press published numerous reports that Jackson had destroyed the natural beauty of his face through obsessive plastic surgery: that he had raised his forehead, widened his eyes, sharpened his cheekbones, reduced or enlarged his lips (both procedures have been confidently asserted), augmented his chin, squared his jawline, and basically removed his old nose and started using a prosthetic one instead. This story was fueled in large part by Jackson himself, but it was picked up and exaggerated in print, television, and online media outlets from Rolling Stone to The Russia Journal, from TMZ to The New York Times.

Importantly, like the Maestro, Jackson both fostered and negated the illusion that he had distorted and destroyed his face. For example, he occasionally wore bandages when there was no physical reason to do so, as three of his bodyguards—Bill Whitfield, Mike Garcia, and Javon Beard—told Ashleigh Banfield of Good Morning, America in a March 9, 2010, interview:

Banfield: Was he concealing an injury with those bandages?

Whitfield: No, that disguise to him was the burn victim look.

Banfield: It was a disguise?

Whitfield: A disguise, to him.

Banfield: When you saw him coming downstairs, getting ready to get in the car with the bandages, what did you think?

Whitfield: Something’s up with him.

Garcia: Yeah, what’s going on?

Whitfield: Yeah, something’s up.

Banfield: Did you ever tell him?

Beard: How could you tell him that? He’s coming down with the kids, so we can’t say, like, What the hell you got on, sir?

Through acts of mystification such as this, with his face frequently hidden by facemasks or bandages or made unfamiliar by makeup, Jackson stoked the rumors of extensive and ongoing plastic surgery.

At the same time, he always said he’d had very little plastic surgery, and his mother confirmed this after he died. In a November 8, 2010, interview, Oprah Winfrey asked her, “As he continued to have other operations and changed the way he looked, did you feel like you could say something to him about that?” Mrs. Jackson responded, “He had other operations on his nose, but any other thing, he didn’t, except his vitiligo.” In addition, many of Jackson’s fans have long claimed he had very little plastic surgery, and the photographic evidence supports this.

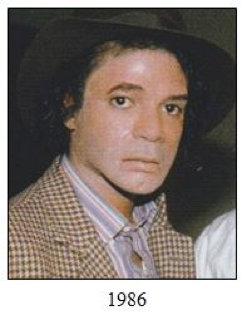

There are times when his face does seem remarkably unfamiliar, almost unrecognizable. In fact, his brother Jermaine writes in his book, You are Not Alone: Michael, through a Brother’s Eyes, that on at least one occasion even he didn’t recognize him. During intermission at one of Jermaine’s concerts, a “pasty-looking white man, aged in his forties, wearing a hat and looking a bit long in the face” told him he was “a huge fan” (275). Jermaine shook his hand and thanked him, “and everyone burst out laughing.” The “pasty-looking white man” was his brother, Michael. Here’s a picture of Michael Jackson taken that night in Jermaine’s dressing room:

As this picture demonstrates, it isn’t just superficial traits like the color of his skin that’s changed, but the apparent structure of his face as well. His angular chin has become much more rounded, almost puffy, and seems longer somehow. (That may be why Jermaine describes him as “a bit long in the face.”) The hollows beneath his cheekbones have disappeared, and his cheeks appear much fuller—more like they did when he was a child. His eyebrows have lost the high arch he inherited from his father. And the shape of his nose has changed completely: his nose never looked like this, either before or after surgery. Jermaine writes that even after staring at this face intently, it was still “unbelievably unrecognizable” (275). This was in May 1986, only 2½ years after Thriller was released and long before the plastic surgery scandal became a media obsession, yet Jackson was already very skilled with disguises and used them often. As Jermaine goes on to write, “During the Bad tour, it was this disguise, along with others, that allowed him to mingle and sight-see among crowds in places like Vienna and Barcelona.”

This ability to disguise his appearance so completely his own brother couldn’t recognize him—even altering the shape of his features and the apparent structure of his face—raises some very intriguing questions, especially in light of the artistic strategy he maps out in Ghosts. Did Michael Jackson have extensive plastic surgery in the 1990s and 2000s, as the tabloids and even the mainstream media reported again and again? Or was the plastic surgery scandal an extreme act of performance art? Specifically, was it a performance designed to bring about important emotional and psychological changes in us, his audience—an audience who, like the villagers in Ghosts, threatened a “Maestro” with irrational and hysterical fears?

The photographic evidence reveals fascinating clues. For example, here are two photos taken in 1987 and 2003—a 15-year period when Jackson reportedly had as many as 50 plastic surgeries—and at first glance his face does appear radically changed:

However, a closer examination reveals that, as in Ghosts, it’s all just an illusion—mainly the skillful use of misdirection and makeup—not plastic surgery. If we compare his features in 1987 with his features in 2003, they are identical. His forehead, eyes, cheeks, lips, chin, and jawline are unchanged. Even his much-maligned nose looks pretty much the same.

Here are three more images taken from a different angle. These images cover an even longer timespan—26 years—but again the structural lines of his face appear unchanged:

The first is a candid photograph taken in 1983, the year Thriller was filmed; the second is a screen capture from a 1999 MTV interview, at the height of the plastic surgery scandal; and the third is a candid photograph from 2009, not long before he died. However, except for a smaller nose and a cleft in his chin—changes Jackson himself acknowledged in his 1988 autobiography, Moonwalk (229)—his features in these three images look the same. I see no changes to his forehead, his eyes, his cheeks, his lips, his jaw line. And when I watch video footage of him from over the years, his face is expressive and animated. It is not the “frozen” face of plastic surgery. Taken together, the video and photographic evidence contradicts the rampant media reports that he “ravaged” his face through obsessive plastic surgery and confirms what Jackson and many of his fans long said: he changed the shape of his nose and added a chin cleft in the 1980s, but made no noticeable structural changes beyond that.

Like the unfounded accusations of witchcraft in 1692 and molestation in 1993, the accusations of excessive plastic surgery were primarily a case of mass hysteria. But like Tituba 300 years before him, Jackson wrested some degree of control over those accusations and then, through his skill as a storyteller and an artist, rewrote that narrative to reflect our own fears back at us. In other words, if we were going to insist he was a monster, then he’d give us a monster. Like Tituba, he’d accept and inhabit the role of Other that was being imposed on him, and then mesmerize us with our own fantasies brought to life and magnified to nightmarish proportions. However, there’s a critically important difference between them: while Tituba inadvertently inflamed the hysteria that threatened her and the other residents of Salem Village, Jackson redirected and diffused it. As he suggests in Ghosts, he commandeered the plastic surgery scandal as a remedy to the mass hysteria surrounding the claims he’d corrupted a child and, in effect, used one scandal as a firebreak to help contain the other.[7]

Ghosts therefore provides fascinating insights into Jackson’s analysis of his particular case as well as mass hysteria cases in general, and posits the plastic surgery scandal as an artistic response to that hysteria. Over time, Jackson transformed his face into a powerful work of art that exposes the groupthink underlying mass hysteria and reveals just how fully our beliefs shape our perceptions. In effect, his face became a mirror that reflected the biases of each individual viewer. Those conditioned by the popular press to see a face ravaged by plastic surgery saw a face ravaged by plastic surgery, while those predisposed to see a beautiful face saw a beautiful face. This in turn mirrored other biases viewers imposed on him. Those who thought he was a freak and a pedophile saw a freak and a pedophile. Those who thought he was a victim saw a victim. And those who thought he was a champion of the powerless, the oppressed, and anyone outcast by fear or prejudice—especially prejudice about difference and the “proper” expression of race, gender, and sexuality—saw a champion.

Apparently, this function of reflecting the preconceived ideas viewers imposed on him was not accidental. Jackson appears to explain his intentions fairly explicitly in “Is It Scary,” one of the songs featured in Ghosts:

I’m gonna be

Exactly what you wanna see

It’s you who’s haunting me

Because you’re wanting me

To be the stranger in the night

Am I amusing you?

Or just confusing you?

Am I the beast you visualized?

And if you wanna see

Eccentric oddities

I’ll be grotesque before your eyes

Let them all materialize (Jackson 1997a)

Thus, those who insist on seeing him as a “beast” and a pedophile—a “stranger in the night”—will see a reflection of the monstrous image they are imposing onto him. As he repeatedly sings, “I’m gonna be / Exactly what you wanna see.” He also predicts, “if you wanna see / Eccentric oddities / I’ll be grotesque before your eyes”—a prediction that proved true for many observers.[8]

However, as he goes on to say, different people will see different things based on their expectations:

So did you come to me

To see your fantasies

Performed before your very eyes?

A haunting ghostly treat

The ghoulish trickery

And spirits dancing in the night?

But if you came to see

The truth, the purity

It’s here inside a lonely heart

So let the performance start

So those who “come to me” expecting a “a haunting ghostly treat” will witness the deliciously frightening spectacle they anticipate, while those who approach him expecting to see “truth” and “purity” will find them “inside a lonely heart.”

After explaining his intentions, he then challenges us with three unsettling but crucially important questions:

So tell me

Is it scary for you, baby?

Tell me

So tell me

Is that realism for you, baby?

Am I scary for you?

Taken together, the lyrics of “Is It Scary” force us to reexamine everything we think we know about Michael Jackson. Was his life as it was portrayed in the media real, or was it “realism”—an artistic creation disguised as reality? Were the stories of “eccentric oddities” real, or were they “ghoulish trickery”? Were the photos of a “grotesque” face real, or were they a reflection of “what you wanna see”? In other words, to what extent was the story of Michael Jackson as it was portrayed in the media based on fact, and to what extent was it a “performance” orchestrated by an entirely new kind of artist—an artist who, like Tituba before him, “created a new idiom of resistance”?

I believe that over the course of his career, beginning in the 1980s with tabloid articles about the hyperbaric chamber and the Elephant Man’s bones and Bubbles the chimp and extending throughout the remainder of his life, Jackson was actively engaged in a new genre of art—one where his medium consisted not of music or paint or film but of the paparazzi, the tabloids, celebrity television shows, and even the mainstream press.[9] They became his palette for expressing a new art of celebrity and identity. Through them, he created an ephemeral public persona notable for its “eccentric oddities” and epitomized by his ever-present yet ever-shifting face and body: a public image that is both ubiquitous yet polymorphous, impossible to escape yet impossible to grasp, intimately familiar yet startlingly unfamiliar.

We can trace the origins of this new art form, or at least some aspects of it, back many years. For example, the cultivation of a bad boy public image extends back at least to the Romantic poets of the early 1800s. For Byron and Shelley, especially, their daring public personae were intertwined with their art. And there is one modern artist in particular whose work anticipates Jackson’s: the Pope of Pop, Andy Warhol. Like Jackson, Warhol cultivated both an enigmatic public persona as well as an eccentric public appearance. Interestingly, Warhol suffered from auto-immune disorders that attacked the pigment of his skin. He also disliked the shape of his nose and reportedly had plastic surgery to make it smaller and thinner. The 2001 documentary, Andy Warhol: The Complete Picture, includes photographs of Warhol from the 1950s that show large white patches on his cheeks and neck. It also includes interviews with friends and clients from early in his career who say he was very uncomfortable about his appearance, especially his “bulbous” nose and the uneven pigmentation of his skin. Perhaps motivated by this discomfort, at least in part, he began experimenting with his face and hair, gradually developing a look that combined extremely pale skin with dark, dramatic eyebrows and a series of outlandish wigs. At some point Warhol began viewing his public appearance as part of his art, and even framed some of his wigs to encourage viewers to see his appearance as art.

Jackson characterized his own face as art as well, according to his dermatologist, Dr. Arnold Klein. In a November 5, 2009, interview, Klein told Harvey Levin of TMZ that Jackson “viewed his face as a work of art. You have to understand. It’s hard to … understand this, but he really viewed his face as a work of art, an ongoing work of art.” Jackson subtly suggests this in his short films as well, particularly Ghosts, Scream, and Black or White. And he seems to acknowledge Warhol’s influence in Scream when his onscreen character studies three images: an abstract painting by Jackson Pollock, a surrealist painting by René Magritte, and a self-portrait by Andy Warhol—specifically, a black-and-white photograph of Warhol’s face. It seems significant in this context that Jackson did not include one of Warhol’s paintings or silkscreens in this sequence. Rather, he chose a photograph of his face, suggesting that he saw Warhol’s face as an important work of art—as important as the paintings of Pollock and Magritte.[10]

All of this leads to a radically expanded delineation of the range of Jackson’s art, redrawing the boundaries of his career to include not only his contributions to popular music, dance, film, and fashion, but also his development of a richly complex art of celebrity and identity—a performance of identity that challenges normative conceptions of race, gender, sexuality, nationality, religion, family, and other patriarchal social structures, all while fiercely defying the very idea of “normal.” Based on this expanded definition of his art, I have come to see Michael Jackson as the most important artist of our time, with the King of Pop surpassing the Pope of Pop in the reach of his artistic understanding, the importance of his ideas, and the deep cultural shifts he helped bring about, particularly the way we perceive and experience difference. I suspect future generations will look back and interpret his changing appearance and “eccentric oddities” very differently than we do today, and I believe they will see his face as his masterpiece.

However, his face—or more precisely, the way he choreographed our constantly shifting perceptions of his face—is a work of art unlike any we’ve ever seen before, of a scope and genre unlike any we’ve ever seen before, and I believe it has the potential to fundamentally alter how we perceive, interpret, and experience our world. It’s a work that both evokes and contests some of our deepest prejudices, forcing us to look at our own reflections and question our own motives, responses, and beliefs. For example, when confronted with the changing color of his skin, what exactly did we feel (pity? contempt? shame? sorrow? embarrassment? guilt? maybe even a smug superiority?) and what do those emotions tell us about how we read and interpret racial differences? When evaluating the plastic surgery scandal and other scandals surrounding him, whom did we believe, whom did we treat with skepticism and disdain, and on what basis did we make that distinction? And when contemplating the idea of a black man “turning white,” what was so very threatening about that—so threatening he was publicly castigated for it for more than two decades—and what accounts for the rather fevered insistence that a black man must stay black? His ever-shifting face—or rather, our ever-shifting interpretations of his face since his actual face changed very little—is a work that unhinges perception, frays the linkages between signifier and signified, and defies the many cultural narratives imposed on him and his body: narratives of race and gender, sexuality and criminality, and ultimately identity itself. It’s a work so revolutionary it requires new tools and new interpretive strategies to understand it.

The preliminary stages of developing new critical approaches to interpreting Jackson’s cultural significance—particularly the significance of his face, his body, and his public image more generally—have already begun. There is now a growing body of criticism that grants Jackson some degree of agency in creating and cultivating his persona, and some of this analysis begins to explore his public face and “eccentric oddities” as both transgressive and potentially liberating. However, as with critics in general, both in academia and in the mainstream media, these authors—without exception—buy into the false narrative of excessive and ongoing, even self-mutilating plastic surgery. As a result, they invariably see in Jackson’s face evidence of something pathological—a uniformity of opinion that exasperates Jackson’s fans. These alleged pathologies include a hatred for himself, his father, his race; a fetish for youth, Peter Pan, Diana Ross; a morbid fear of adolescence, including sexual maturation and possible changes in his voice; a morbid fear of wrinkles and old age; a symptom of childhood physical abuse, psychological abuse, possibly sexual abuse; a childhood lost to work and the stage; the isolation and idolatry of celebrity; an obsessive perfectionism coupled with a vague “addiction” to plastic surgery; as well as more clinical-sounding diagnoses such as narcissism, anorexia or bulimia, and even body dysmorphic disorder. The sheer number and variety of these armchair diagnoses underscores their speculative nature and suggests they reveal at least as much about the anxieties of the viewer as the supposed inner demons of the viewed. However, if we set aside these judgments and the incorrect assumption underlying them—namely, that Jackson had extensive and disfiguring plastic surgery—it reveals some very interesting and important work.

For example, in Negotiating Difference: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Positionality, Michael Awkward opens up possibilities for seeing Jackson’s face as a work of art—one that potentially rebukes his critics for imposing their “limited notions of blackness” onto him:

[D]oes his stance serve as a critique of other’s critiques of his putatively deracializing transformations by suggesting … that the human body has come to represent an extremely malleable surface and that others’ efforts to read his altered state as a manifestation of an absence of racial pride are themselves operating in terms of limited notions of blackness? … In ways that strike me as potentially profound, Jackson’s image might be said to constitute a fundamentally artistic effort. (184)

This could be a productive approach to begin to understand Jackson’s public image as “a fundamentally artistic effort,” particularly his disruptions of how race and gender are signified by his face and persona: not by conjecturing what those disruptions tell us about Jackson’s psychological state (did he hate his father? his race? himself?) but rather by analyzing why those disruptions create such tremendous anxiety within us, his audience, and what that anxiety tells us about our attachment to normative constructions of identity.

This is precisely the task Julie-Ann Scott sets for herself in “Cultural Anxiety Surrounding a Plastic Prodigy: A Performance Analysis of Michael Jackson as an Embodiment of Post-Identity Politics.” Unfortunately, while Scott critiques the tendency to view his face as “the manifestation of personal psychoses” (169), she can never quite rid herself of that tendency. (She includes an extended discussion of body dysmorphic disorder in her article.) Even the stated goal of her investigation reveals just how fully her project is influenced by a mournful dismay at his presumed self-mutilation: “Through this analysis I will not seek to provide answers as to why Jackson’s face morphed.… I am interested in how our attention shifted between celebrating his music and grieving his changing face” (168). However, if we can separate out and adjust for the language of pathology that appears throughout her article, Scott provides some very useful insights into the performative function of Jackson’s public image.

For example, Scott asserts that his ambiguity is so very threatening in part because it forces us to question the cultural foundations of our own identities—questions that are especially fraught at this historical moment as we seek to deny the significance of race, gender, and age in determining identity:

In our interrogations of Jackson, asking him if he is trying to be white, feminine or childlike, we are performing our own struggles surrounding these categories. When a body defies that which is deemed natural, we are forced to question meanings we have come to depend upon, to grapple with the fragility of that which we achingly wish to be true. Our berating of Jackson for defying identity categories crystallizes the importance we place upon them in our daily performances of self and culture, reminding us that the categories we struggle to render irrelevant still matter to us, and matter deeply. (178)

So while Scott does not see Jackson’s face and public persona as art but rather as interesting side effects of his presumed psychological disorders, she nevertheless sees his face and persona functioning as meaningful art often does. Specifically, they force us to question some of our most deeply held beliefs and assumptions—culturally produced articles of faith that have become so entrenched we may not see them as cultural constructs but rather as something true and natural, as Scott describes:

Cited and re-cited performativities become shared cultural performances, shared narratives of who we are.… Performances that challenge these narratives, such as Jackson’s changing face, disrupt categories of race, gender and age [and] are met with resistance as we collectively struggle to defend what we know to be true. (171, emphasis hers)

Viewed in this way, the intensity of the backlash to Jackson’s evolving public image is itself a testament to the revelatory power of his face as art. As Scott writes, “We do not seek to diagnose Jackson as medically and psychologically ill simply out of curiosity or concern but rather to mitigate the unsettling power of his performance” (179)—a “performance” of identity that I would call art.

Harriet Manning grants Jackson much more volition as an artist and places his complex enactment of identity within a broader historical context in Michael Jackson and the Blackface Mask. In Manning’s view, Jackson performs his identity as a constant mediation between the historical narratives forced onto him and the counter-narratives he created in response. Focusing primarily on Ghosts and the “panther dance” at the end of Black or White, Manning interprets Jackson’s face and dance moves as actively evoking, engaging with, and subverting the legacy of blackface minstrelsy—a legacy that has allowed whites to define what it means to be black for nearly 200 years. As Manning writes in her analysis of Black or White and the public outcry that followed its release,

Jackson in the panther dance acts out ideas of blackness constructed on the minstrel stage by and for whites yet his faithful adherence to these today is apparently intolerable: Jackson’s chest rubbing and fly zipping are punishable offenses yet were the sort of black male masturbatory signs that had been adored in classic minstrel caricature. The negative response is contradictory not only because Jackson is giving others outside his own subjectivity what they traditionally constructed, desired and enjoyed but also because such notions concerning blackness and especially black masculinity still inform popular ideas about the same today. (41)

In this way, Jackson enacts tropes of black male hypersexuality as a raging, barely contained, rarely sated, animalistic appetite—tropes that were forged on the minstrel stage and are still very much alive today, as Manning illustrates through her analysis of hip hop. (As Manning makes evident, it is this characterization of black masculinity as oversexed, violent, unfeeling, uncaring, uneducated but street savvy that allows music critic Eric Olsen to state, “Eminem is far blacker than Michael Jackson.” It is only within the context of blackface minstrelsy and the resulting tropes of black masculinity that still inform public opinion today that this statement makes any sense [136].) In the panther dance, Jackson exaggerates the narratives that whites have imposed on black men’s bodies for nearly two centuries and then reflects those inflated stereotypes back at his predominantly white MTV audience, forcing that audience to confront prejudices that lie just beneath the surface of modern conceptions of black men and black male sexuality.

Manning also sees Jackson’s face as a kind of “whiteface mask”—an exaggeration of whiteness that highlights and resists racial essentialism and white ideals of beauty while appearing to conform to those ideals. As Manning notes, “His skin is not just pale but porcelain white” (44), and she later claims that he “denies absolute racial difference through surgical choices in his face” (48). Importantly, since the 2013 publication of her book, Manning has revised her thinking about the extent of Jackson’s plastic surgery, as she discusses in an April 10, 2014, post at Dancing with the Elephant:

Perhaps, because racial identity by appearance is still so fundamental to our perception of others, racial facial features (in Michael Jackson’s case, skin colour and nose shape) are processed by our brains as being “bigger,” more all-encompassing than they actually are. So, even when a face has otherwise not changed much, if these particular features—these strong racial signs—are altered, the perception is that the whole face has radically changed, when in fact it has not.

So as Manning suggests, by confusing the “strong racial signs” we use to determine racial identity and affiliation, Jackson profoundly altered how we read his face. This created the perception that the physical structure of his face had changed, “that the whole face has radically changed, when in fact it has not.” In other words, it wasn’t his face that changed but how we interpret it. This is a fascinating line of inquiry that invites further study—one that once again shifts the focus from him to us, from the psychological motivations behind his performance of race and difference to our responses to that performance, as well as its deep cultural impact.

Now that Michael Jackson is gone and the hysteria surrounding him is starting to subside a bit, perhaps we can begin to think more rationally about who he was and what he meant to us. Maybe we can finally develop the theoretical apparatus needed to understand his art, as well as the compassion needed to understand his life. Maybe we can even begin to comprehend and appreciate the artist behind “the performance,” as he calls it in “Is It Scary.” And maybe we can at last begin to take the full measure of just how much he challenged and changed us, and just how much we lost when he died.

“I like creating magic … creating something that’s so incredible, an illusion. To put people in a situation, no matter what it may be, and give them totally the opposite or the unexpected—so much more than what they thought would happen. Whoosh. I mean, just blow their minds. I like creating magic, excellence. I love doing that. Ah, there’s nothing like it.”

— Michael Jackson

Notes

[1] Translation by James S. Williams.

[2] Chandler’s taped conversations with Schwartz have been quoted numerous times (for example, Fischer 1994, 218; Taraborrelli 2009, 477-478; Halperin 2009, 19-20; and even Chandler 2004, 232-241), with some variation in how they are transcribed. In addition, audio excerpts were broadcast by CBS News and others, and some of those audio clips have been uploaded to the internet.

[3] Jordan’s nickname is spelled “Jordy” in the transcript of the taped phone conversations filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court and “Jordie” in the written chronology his father gave to police. The spelling each used was retained when quoting those sources.

[4] I have not seen the KCBS-TV interview, though I have tried for several years. The KCBS-TV video librarian, Allan (he agreed to spell his first name, but declined to give his last name), confirmed they have the segment in their archives but refused to release a copy, even for research purposes. Other attempts through KCBS-TV were unsuccessful as well. I then tried to obtain a copy through Thought Equity Motion, the company that handles licensing agreements for CBS. They do provide review copies for research; however, since the story was not picked up nationally but was only carried by KCBS-TV, a Los Angeles affiliate, KCBS-TV retains licensing rights and they refused to release it to Thought Equity Motion. I then contacted two authors who have published slightly different descriptions of the KCBS-TV interview: Mary A. Fischer and Ian Halperin. Halperin didn’t respond, but Fischer did. In an in-depth article published in the October 1994 issue of GQ magazine, Fischer reports that a KCBS-TV newsman asked Chandler about his son’s sedation, and Chandler answered that “he did so only to pull his son’s tooth and that while under the drug’s influence, the boy came out with allegations” (221). When I asked Fischer about this, she said she did not have a copy of the KCBS-TV interview but she had watched it, and she stands by her article.

Fischer and Halperin disagree on one point: whether Chandler confirmed that Jordan was under the influence of sodium Amytal when he made the allegations. Sodium Amytal is a psychiatric drug that was once considered a potential “truth serum” but later became implicated in producing false memories because it leaves those under its influence extremely vulnerable to suggestion. In fact, a number of high-profile court cases in California in the 1990s dealt specifically with sodium Amytal and false memories of sexual abuse. Fischer and Halperin agree that the KCBS-TV reporter asked Chandler if Jordan was given sodium Amytal; however, while Fischer says Chandler confirmed it (221), Halperin says he merely confirmed the use of “a drug” without specifying which one (44). Later, while researching her article, Fischer asked Torbiner if he gave Jordan sodium Amytal, and she reports that he neither confirmed nor denied it, saying, “If I used it, it was for dental purposes” (221)—an odd statement since sodium Amytal is a psychiatric drug. Regardless of which drug was used, both Fischer and Halperin report that Chandler told the KCBS-TV reporter the allegations were made while Jordan was still under sedation.

[5] In an April 2003 Vanity Fair article, Maureen Orth reported that Jackson hired a “witch doctor” or “voodoo chief” in the summer of 2000 to bring about the death of “25 people on Jackson’s enemies list,” and that in pursuit of this morbid goal the witchdoctor “ritually sacrificed” 42 cows as well as chickens and other animals. According to Orth, this carnage occurred in Switzerland; however, a spokesman for the Federal Office for Agriculture (FOAG) in Switzerland expressed skepticism when told of Orth’s article. Switzerland has a rigorous cattle identification and registration program that tracks every cow from birth through slaughter and processing, and they have been especially vigilant since the “mad cow” or BSE crisis in the mid-1990s. However, the FOAG has no knowledge of an event such as Orth describes, nor any evidence indicating that such an event might have occurred.

[6] Since Jackson’s death in 2009, two other accusers—Wade Robson and James Safechuck—have alleged they were sexually abused by Jackson when they were children. Both Robson and Safechuck were deposed during previous investigations, and both swore under oath that Jackson never acted improperly toward them. Robson also testified during the Arvizo trial when he was 22 years old, and was asked detailed questions about his relationship with Jackson: “did Michael Jackson ever molest you at any time?” “did Michael Jackson ever touch you in a sexual way?” “has Michael Jackson ever inappropriately touched any part of your body at any time?” “Did he ever kiss you on the lips?” “would you ever cuddle in bed?” “Would you lie next to one another?” and “Would you touch?” Robson answered “No” to all of these questions. He was also asked, “Has anything inappropriate ever happened in any shower with you and Mr. Jackson?” and he replied, “No. Never been in a shower with him” (Reporter’s Transcript 2005, 9097-9132). And in the days and weeks after Jackson’s death, Robson praised him in numerous interviews. For example, on June 27, 2009, he told Peter Mitchell of the Melbourne Herald Sun that Jackson “is the reason I dance, the reason I make music, and one of the main reasons I believe in the pure goodness of humankind.” On August 14, 2009, he told Entertainment Tonight, “with Michael, I just had a wonderful relationship. I learned so much from him. As an artist, and as a kind human being.” And for the September 2009 issue of Dance Magazine, he told Kina Poon, “I learned altruism from him. In the entertainment industry, it’s easy to get jaded. Despite all of the madness he went through, he had such an innocence. He trusted people, and in his heart, believed in them.” However, Robson now says Jackson molested and raped him, and all of the things he denied in court did happen. His lawyers filed a financial claim against the Jackson Estate on May 1, 2013, and petitioned the court to allow Safechuck to join Robson’s claim in July 2014.