Entangled Complicities in the Prehistory of "World Music": Poul Rovsing Olsen and Jean Jenkins Encounter Brian Eno and David Byrne in the Bush of Ghosts

Steven Feld

Professor, University of New Mexico and University of Oslo

Annemette Kirkegaard

Associate Professor, University of Copenhagen

The label “world music” is today so

naturalized,

both in the academy and marketplace, that it is sometimes hard to grasp

how different the world and the music referenced by the conjoined term

once was (Born and Hesmondhalgh 2000, Erlmann 1996, Feld 2000,

Giannattasio 2003, Guilbault 1993, Martin 1996, Taylor 1997, 2007,

White 2011). A potent way to engage that history is through detailed

case study of early moments of conjuncture. We do that here to review

how academic practices of non-western music collection and presentation

were transformed by new regimes of “world music”

industrialization and representation. The study of these

transformations indicates how once-sharp contrasts became blurred

complicities that led to both contestation and critique.

The specific “world music” story we examine

concerns the intertwining of two LP recordings, The Human Voice in the World of

Islam (Jenkins and Olsen 1976a) and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

(Eno and Byrne 1981). The former was produced through a nexus of 1970s

academy, archive, and museum ideals of academic folk music curation.

The latter was produced at the technological cutting-edge of

early-1980s Euro-American elite art-pop. To understand the contact

process, and the consequent ethical, legal, aesthetic, cultural, and

political discourses that were set into motion, we begin at the site of

rupture.

Schizophonia and

its Discontents

Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer coined the term schizophonia

(1977:90) to refer to the splitting of sounds from their sources. What

he had in mind was the technological process of sound recording. The

nervousness of his schiz-word captured the modernist worry that

splitting means loss, a diminution in the relationship between a

“live” original and it's technologically mediated

double. But what about the possibility that schizophonia might signify

as much about amplification as it does about diminution? This takes us

to the considerably more complex dialectic that proceeds from the

ontology of the split, the possibility for new circulatory lives, for

new social and aesthetic meanings.

What happens when the contents of once-more-marginal

“ethnographic” recordings are renegotiated? What

happens when “other” voices and sounds are

variously edited, copied, or sampled for incorporation into highly

commercial pop or avant-garde productions with different aesthetic

agendas, global circulatory routes, and ownership regimes? What is

amplified by this kind of sonic recontextualization and resignification?

Feld’s “world music’” essays

(1988, 1994, 1996, 2000) argue that this is where schizophonia becomes

schismogenesis, a spiraling and intertwining mutualism of difference

heightened and difference denied. And what it produces is a discourse

of anxiety. It is the anxiety that “world music”

rests on economic structures that turn intangible cultural heritage

into detachable labor. It is the anxiety that this detachability

marginalizes, exploits, or humiliates indigenous originators. It is the

anxiety that elite pop artists and global corporations are

consolidating music ownership in centers of power while promoting

leisure audio-touristing.

But Feld’s argument is that alongside the production of these

anxious narratives, “world music” discourse has

consistently, indeed, dialectically, produced a much more frequent

narrative, of celebration. Celebratory narratives see “world

music” as indigeneity’s champion and best friend.

Celebratory narratives see musical hybridity and fusion as cultural

signs of unbounded and deterritorialized identities. Celebratory

narratives see the production of both indigenous autonomy and cultural

hybridity as unassailable global positives, moves that signify the

desire for greater cultural respect and tolerance. Celebratory

discourse virtually proclaims “world music”

synonymous with anti-essentialism, with the hope of greater cultural

equilibrium amidst difference.

Kirkegaard, from a slightly different but similarly critical angle, has

since 1981 studied the development and contact of East African popular

musics –primarily taarab and coastal dance musics- with the

“world music” market. The celebration of otherness

is central to her research, and drawing on theories by Erlmann (1993),

Hannerz (1992), and Feld (1994), she has examined issues of cultural

identity (2002), tourism, (2001), festivalisation (2005), revival and

conservatism, and cultural flows. Her ongoing research highlights the

responses of “third world” artists to the

structures and conditions of global music production. Tracing the

disciplining effects of the asymmetric flows of communication, she

explores the production of desires among Western audiences for

“authentic” soundscapes in “small

countries” (Wallis and Malm 1984, Malm and Wallis 1993). Her

recent studies of WOMEX (World of Music Exposition), and its

antecedents focus on the continuum of diversity and sameness (2008,

2009, forthcoming B) examining how conservatism in “world

music” business practices lead to a renewed focus on

stylistic “roots” and historicized genres.

In 2004 Feld began to investigate the history of Brian Eno and David

Byrne’s My

Life in the Bush of Ghosts (henceforth MLBG), a 1981 LP

re-released as a CD in 1990 and in an enhanced 25th-anniversary edition

in 2006. His concern was MLBG’s

incorporation of sounds from Islamic religious discourse into popular

music, viewed as part of the larger Western avant-garde legacy of

primitivist and exotica projects (Bellman 1998, Born and Hesmondhalgh

2000, Erlmann 1993, 1996, Feld 1996, Hutnyk 2000, Taylor 1997, 2007,

Toop 1995, 1999). He focused on the censorship of

“Qu’ran,” the MLBG track where Eno and

Byrne used dance grooves to ornament an excerpt of Quranic recitation,

recorded in Algeria in 1970 by Jean Jenkins, and originally published

as the first track of the LP The

Human Voice in the World of Islam (henceforth HVWI).

In 2004, Feld presented his work on MLBG, HVWI and the

censorship of MLBG’s

“Qu’ran” track at the University of

Copenhagen. That work details how, both in the immediate moment of the

LP’s release, and then in the light of heightened

sensitivities following the Salman Rushdie affair, Eno and Byrne

ultimately removed this track from MLBG’s

CD reissues, even though they mysteriously refused to discuss the

matter for twenty-five years (Feld 2007, 2011). As Feld had only worked

on the story of MLBG’s

“Qu’ran” track, originally recorded by

Jean Jenkins, Kirkegaard offered to join him to research

MLBG’s two tracks that incorporate material from

“Abu Zeluf,” another piece from HVWI, recorded in

Lebanon in 1972 by the Danish composer and ethnomusicologist Poul

Rovsing Olsen.

Kirkegaard went on to work with archival recordings and documents at

the Danish Folklore Archives, Danish Radio, Danish National Archives,

and to interview important witnesses to this history in Denmark. Feld

joined her to interview other key witnesses and to help interpret the

Danish documents alongside his interviews and related documents from

Jean Jenkins’ files at the Museum of Scotland. While drafted

in English by Feld, with a different Danish version by Kirkegaard,

(forthcoming, A), the collective effort is an analytic and interpretive

collaboration sited at the intersection of overlapping histories: of

“world music;” of “folk” music

collection in the UK and Denmark; of the International Folk Music

Council and International Council for Traditional Music; of the

(re)circulation of musics from the Islamic world.

MLBG and

“world music”

“World music” was not quite a market category when MLBG was released

in February 1981 by Eno’s EG Records. But the label rather

quickly magnetized its way to the LP because of Eno and

Byrne’s mix of pre-digital ambient atmospherics, electronic

effects, multi-track processing and bass and percussion dance grooves

together with what they and others called “found

sounds,” excerpts of radio shows taped off-air, and from

ethnographic field recordings. MLBG’s

radio segments came from call-in shows featuring indignant hosts,

politicians, evangelists, and Christian preachers. The ethnographic

recordings came from three LPs, one a compilation of Islamic vocal

practice, The Human

Voice in the World of Islam (Jenkins and Olsen 1976a), one

featuring African American Georgia Sea Island singers (Moving Star Hall

Singers 1964), and one an anthology of popular Arabic singers (El

Atrache et.al., 1976).

While, in Timothy Taylor’s words, the MLBG LP

“more than any other demonstrated the usefulness of not just

other sounds, but Others’ sounds – sounds by people

from nonwestern places” (Taylor 2007:133), it was hardly

unique or original in this regard, coming more than ten years after

Holger Czukay’s experiments with “impossible musics

from unknown worlds” (Toop 1995:122) and being clearly

derivative of Jon Hassell’s “fourth

world” notion of a “coffee-coloured classical music

of the future” (Toop 1995:122-123), a concept manifest the

previous year,1980, on Hassell’s Fourth World-Possible Musics

LP, also a collaboration with Eno. Still, MLBG certainly

heralded a great deal of what was to come in the 1980s and 1990s under

the banners of “world music,” “global

fusion,” “world beat,” or

“ethno-techno.”

MLBG

joins Eno and Byrne as art school rockers,

visual-conceptual-performance artists who came to concentrate on music.

Brian Eno’s solo projects clearly established him as an

avant-garde electronics and ambient pioneer influenced by Karlheinz

Stockhausen and John Cage (Tamm 1995). David Byrne similarly emerged

during the late 1970s as leader of the hugely popular art-rock group

Talking Heads (Steenstra 2010).

MLBG

was recorded in 1979 and 1980, after Eno moved to Soho, in Lower

Manhattan, New York, from the UK and got involved with Byrne and New

York’s downtown performance scene. With Byrne he co-produced

Talking Heads’ More

Songs about Buildings and Food (1978) as well as Remain in Light

(1979). He then produced, co-wrote songs for and performed on Talking

Heads' Fear of Music

(1980). Like producer George Martin during the Beatles late 1960s

studio period, Eno became, through 1979 and 1980, a de-facto member of

Talking Heads, and on Remain

in Light and Fear

of Music one can implicitly hear the African and Arabic

music traces that relate to his and Byrne’s emergent

enthusiasm for non-western musics.

In an interview with KPFA’s Charles Amirkhanian in February,

1980, a year before the release of MLBG,

Eno presented the idea of “fourth world” music as

“music that is done in sympathy with and with consciousness

of music of the rest of the world, rather than just with Western music

or just with rock music. It’s almost collage music, like

grafting a piece of one culture onto a piece of another onto a piece of

another and trying to make them work as a coherent musical idea, and

also trying to make something you can dance to” (quoted in

Tamm 1995: 161). Likewise, he developed a line of thinking that merged

music technologies with bio-evolutionary metaphor: “What I am

arguing for is a view of musical development as a process of generating

new hybrids” (quoted in Tamm 1995:60).

From February 1981, MLBG

circulated widely in the US and Europe and was broadcast extensively.

In October 1990, the LP was re-released on CD in the US with its eleven

original tracks intact, plus an additional bonus track. In March 2006,

the CD was re-released in an extended 25th-anniversary edition with

additional sound, liner, and video enhancements. The re-publication

speaks both to the project’s commercial success and to the

durability of its makers. After a twenty-seven year break, Eno and

Byrne reunited in 2008 to record and tour with Everything That Happens Will

Happen Today (Helmore 2009).

HVWI, Jean Jenkins

and Poul Rovsing Olsen

The Human Voice in

the World of Islam, the source LP for three MLBG tracks, was

the first volume of Music in the World of Islam (MIWI), a six

LP anthology (currently available as three Cds) on music in the Islamic

world, edited by Jean Jenkins and Poul Rovsing Olsen. Published on

Tangent Records, it was accompanied by a book, Music and Musical Instruments in

the World of Islam, and major exhibit of instruments and a

festival at the Horniman Museum in London (Jenkins and Olsen 1976 a,

b). The project was funded and produced by the UK-based World of Islam

Trust. Jean Jenkins (1922-1990) was keeper of instruments from

1954-1978 at the Horniman Museum and was the major contributor and

editor of the Music in

the World of Islam project (Topp Fargion 1995,

Dijkstra-Downie and Bicknell 2007). Her collaborator, Poul Rovsing

Olsen (1922-1982), was both a composer of contemporary art music and a

scholar of Arabic musics, and was employed for the majority of his

professional career, from 1960-1982, at the Dansk Folkemindesamling

(Danish Folklore Archives, DFS) in Copenhagen. From 1969 he was also

employed as a teacher of ethnomusicology at the University of

Copenhagen (Olsen 2002:6-15).

Of the three MLBG

songs that take recorded segments from HVWI, track 3,

"Regiment" (credited to Eno, Byre, and Busta Jones, with arrangement by

Eno, Byrne, Busta Jones, Chris Frantz, and Robert Fripp), and track 8,

"The Carrier" (credited to Eno and Byrne) both incorporate material

from the song “Abu Zeluf,” sung by a woman named

Dunya Yunis. The song was originally recorded in Beirut in 1972 by

Olsen. “Regiment” draws on the song’s

first section, improvised in maqam rast; “The

Carrier” draws on a second section, a metered folk song.

Jenkins’ LP sleeve notes to HVWI identify Dunya

Yunis as "a

girl from a northern mountain village” in Lebanon. On the My Life in the Bush of Ghosts LP,

as well as subsequent CD versions, Eno and Byrne's list of "Voices"

cite the source as "Dunya Yusin, Lebanese mountain singer" (with her

surname misspelled). The original Tangent LP title and album number is

also cited, but Eno and Byrne’s notes do not identify the

song’s original recordist. New liner notes to the 25th

anniversary reissue (Toop 2006) misattribute the recording of

“Abu Zeluf” to Jean Jenkins.

In terms of the presence of material from “Abu

Zeluf” on MLBG,

it should also be noted that “Regiment” became one

of the LP’s most commercially and aesthetically successful

tracks, and one of its most frequent airplay items over the

recording’s history. The strength of this track was heralded

a year in advance of the LP’s release, in a February 14, 1980

interview for Melody

Maker, where Brian Eno spoke to John Orme about the

emerging MLBG

project:

BE: "The two tracks that work really well for me are 'Moonlight In Glory' and 'Regiment'. I think those are the two real achievements of the album, and I think my synth solo on 'Regiment’ is possibly the best I've ever played. People think it's a Fripp guitar rip-off; it really is me on synthesizer."

Poul Rovsing Olsen

and the recording of “Abu Zeluf”

Olsen voyaged in February and March 1972 for a six-week recording trip

to Abu Dhabi and Bahrain in the Arabian Gulf, supported by the

Carlsberg Foundation and the Rask Ørsted Foundation (Olsen

2002:9). The trip began in Beirut where he was to be met and

accompanied to the Gulf by a colleague, Simon Jargy, a French Arabicist

musicologist and Professor of Music at the University of Geneva. But

Jargy was in an auto accident just as Olsen arrived, so for his time in

Beirut, January 26 to February 5, when he departed for Abu Dhabi, Olsen

was hosted by Iraqi oud virtuoso Munir Bashir. Bashir is referred to as

a “good friend” in Olsen’s trip diary;

indeed, the two had a long multi-country relationship as connoisseurs

and curators of Arabic music and Bashir was a frequent visitor to

Denmark (Olsen 1983:1-2).

Olsen’s published diary entry for February 4, the day before

his departure to Abu Dhabi, indicates that he made a casual recording

at midday at Munir Bashir’s office, of a herlig sangerinde,

“a delightful singer,” named

“Dunia” (elsewhere spelled Dunya or Douniah),

described as a twenty-two-year-old

“protégée” of Munir Bashir

(Olsen 1983:5). The diary gives the impression that this was just a

chance encounter. Later in the diary Olsen mentions playing the

recording to positive reception (1983:10). Judging from photographs in

Olsen’s posthumous book Music

in Bahrain: Traditional Music of the Arabian Gulf (2002:

8,14), the original recording was made with a portable monaural Nagra

III reel-to-reel recorder. At the time the Nagra III represented

state-of-the-art technology for professional quality portable sound

recording.

On the original tape held in the DFS collection, Dunya Yunis is

introduced at the beginning of the recordings by Munir Bashir, whose

notes, given to Olsen later that evening in Beirut, identify her as

“Douniah” and her four selections as

“Ataba,” (1:40),

“Ma’anna,” (3:30), “Abu

Zeluf,” (3:00), and “Shru’I”

(2:30). Along with the English notes are Olsen’s Danish

translations. Bashir’s English text gloss is: “You!

The pigeons who send their messages of love. You are the finest kind of

pigeons. I am sure that if you know the case of my love you should have

put me among the feathers of your wings. My body is easier for you to

bear than to bear my best wishes to send it to my sweetheart.”

How did Eno and

Byrne acquire “Abu Zeluf” for MLBG?

Looking through Olsen's papers in the DFS archive, we were specifically

interested to see whether he and Jean Jenkins had correspondence with

EG or Tangent Records, with Eno and Byrne, or with colleagues

concerning the incorporation of “Abu Zeluf” for the

two tracks on MLBG.

There was nothing to be found, but through inquiry it became clear that

many of Olsen's documents were turned over to the Danish National

Archive ten years after his death. There was also a large amount of

material held in family possession.

Olsen died a year and a half after MLBG’s

release. According to close associates, he was very occupied with

composing at the end of his life. All the same, we were initially

surprised to find nothing at DFS related to how Eno and Byrne

contracted to license “Abu Zeluf.” After all, Olsen

was a DFS employee at the time the recordings were made; he was

travelling as a DFS researcher, and depositing his recorded material in

DFS archives. His DFS collections were carefully annotated, and he kept

meticulous records about numerous professional matters. Most of his

letters are headed by DFS registration numbers. DFS posthumously

published his field diary from this recording trip, which he introduces

with the words “Anyone who wishes some knowledge of the vivid

background to this traditional material collected for the Folklore

Archive will, I think, get some pleasure from reading through the

following pages” (Olsen 1983:1). So why were there no

available DFS documents tracing the matters of license and copyright

that would clarify the contractual relationships of Olsen, DFS, EG and

Tangent Records, Jean Jenkins, and The World of Islam Festival Trust?

One of Kirkegaard’s first responses to the curiosities of

that question concerned an aspect of Olsen’s biography

perhaps less known to (ethno)musicologists, who are generally well

aware of his work both as a scholar and composer (Stockmann 1982,

Johansen 1983). After graduating in music theory and piano from the

Royal Danish Academy of Music in 1946, Olsen completed a law degree in

1948 at the University of Copenhagen. This was followed by composition

studies in Paris 1948-49 with Nadia Boulanger and Olivier Messiaen. But

on return to Copenhagen Olsen was employed for the next ten years by

the Danish Ministry of Education, where he specifically worked (from

1954) on the Danish Copyright Act. From there, in 1960, he began his

employment with the DFS, where he remained until his early death in

1982.

From the standpoint of his professional legal knowledge of copyright

issues it would be highly unlikely that Olsen didn’t pay

attention to the matter of permission for the use of this recording.

And equally unlikely that he would keep no documentation of the matter,

given his scholarly and administrative reputation for archival

precision. Moreover, it would be hard to imagine him approving of how

Eno and Byrne used the source recordings given his public stance on

“protection” of folk musics, well known both in

Denmark and international academic circles.

As a typical example, take a1978/9 interview with a composer colleague

where Olsen is asked of his interest in "ethnic music." He responds

with opposition to the label: "’Ethnic music' is a strange

expression. All music is ethnic in the sense that it originates from

people's reactions to life, that it comes from a certain environment.

This applies to the music of Stravinsky and Armstrong, as well as to

the North Indian instrumental music of Ali Akbar Khan and the East

Greenland songs of Maratse. But when we make expressions like "ethnic

music" we always think of foreign peoples from other continents. And

often enough we do so in a strangely condescending manner. The European

by force wants to expand his European faith all over the world. With

great idealism we cause disasters in the name of Christianity,

mercantilism, or Marxism. Music follows our idealistic crusaders who

wish to make the world one big Americo-European pop circus. It is

imperialism which has won when the Greenlander or South American Indian

makes 'rock' or 'folk' to his own guitar accompaniment. It is sad that

it is like this" (Gudmundsen-Holmgren 1978/9:97).

As another example of Olsen's protectionist sentiments and anxiety

about culture change and emerging indigenous musical fusions with

Western pop, one can cite "The Others," the chapter on acculturation,

contact, and development in his 1974 introductory text Musiketnologi:

"The question could be posed if ethnomusicology as it is known still in

1974 is performing a kind of neo-colonial activity, if in fact the

present Master race (Herrefolk) in ethnomusicology consciously

emphasize those traits in the cultures of the developing countries

which keep them from development…In these very years we can

detect the existence of active forms of spiritual neo-colonialism

backed by power relations and economic factors. The West and its

followers in the rest of the world consciously or unconsciously

exercise an influence, which seeks to transform the other into the

image of the West. The Euro-American musics spread, sometimes in light

disguise, across the larger part of the globe, and succeed primarily

because they represent the rich and the powerful. The new music of the

third world is a result of a spiritual neo-colonialism, and all speech

about its connection to progress is but an effect of Western

know-it-all. Let us remember that ‘progress’ is a

typically Euro-American concept” (Olsen 1974:137).

How are we to gauge this somewhat paradoxical position, critical of the

conservatism of some ethnomusicologists on the one hand, yet equally

resistant to musical interaction and change on the other?

Teresa Waskowska Larsen, currently writing a biography of Olsen,

indicated in conversation that it was highly unlikely that Olsen would

in any way have approved of Eno and Byrne's use of his and Jenkins'

recordings. Indeed, in her view, Olsen was almost a "fundamentalist"

when musical styles were in question. She stressed, parallel to

Kirkegaard's impressions from the academic writings and

Olsen’s professional legacy in Denmark, that he strongly

believed in preserving what he believed to be the

“authenticity” or “purity” of

the musics he was involved with collecting or documenting.

Nonetheless, the “protectionist” stance

with which he was associated can and should be complicated by

Olsen’s position and practice as a composer of contemporary

music. A colleague who worked with him at DFS, Morten Levy, also both a

musicologist and composer, confirmed Olsen’s generally

protectionist attitude on folk music and his negativity toward popular

music. But he also stressed, in conversation with Kirkegaard, the

potential counter-force of Olsen’s identification with elite

avant-gardism in contemporary composition. He said it was therefore

possible to imagine Olsen being less restrictive if he believed MLBG was a serious

experimental work.

This was also the initial perspective offered to us in a 2004

conversation with Danish radio journalist and Freemuse NGO activist Ole

Reitov in his characterization of Olsen’s first response to

the “Regiment” track on MLBG. Indeed, it was Reitov

who, six months after the LP’s release in 1981, first played

the “Regiment” track to Olsen at his DFS office,

and solicited his reactions on the spot and on tape. Reitov remembered

Olsen’s response as measured but positive in the sense that

he understood the recording to be a musical experiment.

Piqued by the tension or contradiction here, that of measuring

experimental excitement against purist protectionism, one can also cite

a corroborating complexity in Olsen’s own compositional

influences, where orientalist procedures, like uses of sounds and

ornamentation or references from Arabic or South Asian music, took on

an avant-garde front, for example, in the “Indian

Dancing” section of the piano work “Many Happy

Returns” from 1971 (Opus 70), or, going back as early as

1951, his hommage to the Indian sarod player Ali Akbar Khan in

“Nocturnes” (Opus 21).

However “protectionist” in his approach to what

was, at the time, largely called “folk music,” it

was well known in Denmark and elsewhere that Olsen was no nationalist.

Nor was he in any way intellectually or musically provincial. And

despite his deep respect for local musical traditions, he was certainly

not in the mold of those in the Nordic countries then who construed

folk music research to be the search for the authentic past of

Scandanavian music. Olsen, rather, had a life-long artistic and

intellectual Francophile profile, hardly typical in Nordic musical

composition or scholarship then or now. And in 1970 he was pro-European

common market. In his radio programs and newspaper columns of criticism

for Berlingske Tidendes

Kronik, he railed against Danish politics and art clinging

to old nationalist and regionalist ideas. Deeply criticizing those who

chose the comforts of smallness and insularity over the possibilities

of discovery, he instead chose the model of internationalist humanism,

urging engagement with modernity beyond locality. This multicultural

humanist stance was also the much-recalled side of Olsen that made him

active in shaping the new scope of the International Council for

Traditional Music, formerly the International Folk Music Council,

during his presidency 1977-1982 (Stockmann 1982).

Further to the

heart of the matter

After mapping the broad surfaces of questions and contradictions posed

by this affair, we contacted Olsen’s widow, Louise

Lerche-Lerchenborg. Long active in the field of contemporary classical

music, Lerche-Lerchenborg has also looked after Olsen’s

estate and personal archive. She was not surprised that we could not

find any documents related to contracts or negotiations between Olsen

and DFS with Eno, Byrne, and EG Records on the one side, or Jenkins,

World of Islam Trust, Tangent Records and its manager Michael Steyn, on

the other. She told us that she had a letter to prove that the

arrangement whereby the recordings were licensed had entirely been made

between Eno’s EG and Tangent Records. Neither Jenkins nor

Olsen, despite their status as editors and recordists, were ever

consulted. She also made it clear from the outset that Olsen was

unquestionably angry and embarrassed by the use of his recording for MLBG.

Lerche-Lerchenborg’s vivid remembrance was that

Olsen’s annoyance was directly related to the feeling that

his personal integrity was blemished by the matter. He was upset that

he would be seen to have violated an honor agreement with and for a

singer he didn't really know, a young woman no less, a matter of social

concern in an Arabic cultural context. Additionally, she suggested,

there was the embarrassment this incident could cause him with his

friend Munir Bashir, as well as with the community of professional

researchers in ethnomusicology, who typically prided themselves on

their ability to protect the rights of those they recorded. The issues

were compounded, she said, by Olsen’s professional

visibility, since he was, at the time of the incident, also the

President of the International Council for Traditional Music.

Finally, Lerche-Lerchenborg confirmed that Olsen was never sent a copy

of MLBG by

Eno and Byrne, or by Tangent when it was released in February 1981. He

only discovered the existence of the recording later, probably in

August of 1981, when the “Regiment” track was

played for him and his reactions solicited in a interview at his DFS

office with Danish radio journalist Ole Reitov. Only after this

exposure did Olsen actually acquire the LP, which remains with

Lerche-Lerchenborg to this day.

This is the background to the letter that Lerche-Lerchenborg showed us

from Olsen to Michael Steyn, head of Tangent Records, written on

January 18, 1982, almost one year after the publication of MLBG, and six

months after the Ole Reitov interview and , and six months after the

Ole Reitov interview and Olsen’s first encounter with the LP:

Thanks for your letter of November 23nd. I will answer it in a short while. To-day (sic) only this: You know probably that a kind of Rock record uses stuff from our Islamic album: Brian Eno/David Byrnes (sic) My Life in the Bush of Ghost (sic), Quite popular in Denmark these days. What about copyright?

Despite the way our research re-opened what were potentially difficult issues about Olsen’s embarrassment, late response, and complicity in this matter, Lerche-Lerchenborg graciously provided documents to help us put the story together. Searching her personal archive, she found that there was no reply from Tangent’s Steyn to Olsen’s January 18 letter for six months, until June 15, 1982, just weeks before Olsen died of an aggressive and recently discovered cancer. In that June 15 letter Steyn acknowledged Olsen’s of January 18 and apologized for his late reply. He informed Olsen that Tangent had been consolidated with Topic Records as of the previous October, 1981, and that royalty statements for the last nine months were forthcoming. He assured Olsen that all future business with Topic would be handled as per the original Tangent contract. His concluding paragraph, in its entirety, is as follows:

As far as the Brian Eno LP is concerned, I originally made no demand for payment, believing that the publicity value would be very good. However, their record has sold very well, and I am negotiating with EG records for a fee. Will report further as soon as I am able.

Notice that Olsen’s question to Steyn,

“what about

copyright?” is not answered; offered instead is a response

about compensation and an excuse about publicity. As a lawyer with

experience in the copyright area, Olsen would certainly have known the

difference between inquiring about the more complex management of

copyright and the less complex matter of compensation from fees.

The questions that must be asked here are obvious: what kind

of contract did Jenkins and Olsen have with Tangent Records? How could

their recordings be given freely by the record company with no regard

to the copyright concerns of recordist or recorded? How could Jenkins

and Olsen, both experienced professionals, be party to a recording

contract with no clear protections about republishing, permissions,

clearances, licenses, and payments to performers?

Did Jenkins and Olsen not know, or simply relinquish their rights? Did

they not pay attention to gaps between standard arrangements of the

time and their responsibilities as collectors, not to mention their own

economic interests?

The letter that Lerche-Lerchenborg showed us is the only document

revealing that Eno and EG Records were granted gratis permission

because of a judgement solely by Tangent’s Steyn that the

arrangement was good publicity for the Music in the World of Islam

series. When Steyn, who died in 1999 and left no further paper trail on

this matter, admitted to Olsen that he was negotiating with EG Records,

it was already seventeen months after the LP’s publication,

and six months after Olsen’s inquiry. Ultimately, all Tangent

got in settlement from Eno’s EG Records was a single one-time

payment of £100. Steyn, likely embarrassed, took no

administration fee for Tangent on this sum, splitting it 50%-50%

between Jenkins and Olsen as compensation for the one song each

recorded that was taken for MLBG.

Contracts, or the

lack of…

In fact, there is a production contract for Music in the World of

Islam. But it was only made between Tangent Records and

The World of

Islam Festival Trust, as outlined in a March 17, 1975 letter from

Tangent’s Michael Steyn to Paul Keeler of World of Islam

Festival. There is no signed contract between Tangent and Jenkins and

Olsen. All that exists is an unsigned and undated draft contract

between Tangent and Jenkins, copies of which were found both in

Lerche-Lerchenborg’s archive and Jenkins’ personal

files. This document indicates that Jenkins and Olsen, as editors,

recordist-collectors, and annotators, are to be paid royalties on all

sales of individual LPs, cassettes, and LP and cassette box sets. The

royalty figure is 10% of UK sales and 7.5% of external sales. These

royalties were to be adjusted according to the percentage of

contribution to the LP recordings, and these proportions totaled for

the overall royalty on LP and cassette box sets.

Working through Jean Jenkins personal files at the Museum of Scotland,

Edinburgh prior to their being catalogued, Feld found Music in the

World of Islam (MIWI) royalty statements from Tangent

Records from

publication in 1976 through March 31, 1981 (the last statement date is

May 18, 1981). Volume 1, The

Human Voice in the World of Islam, is

indicated as the LP with the most equal percentage of recorded

contributions from the two collaborators.

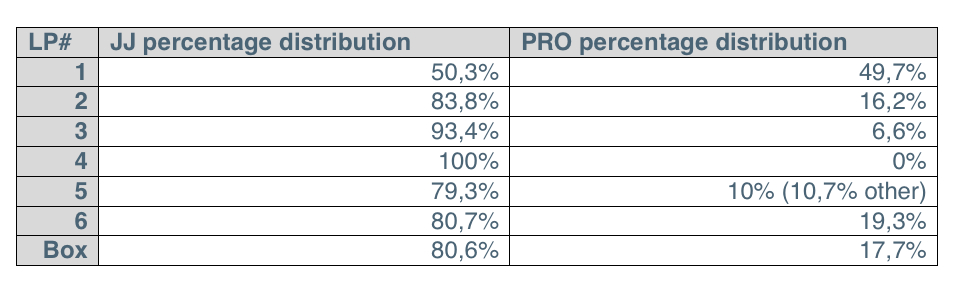

Jean Jenkins thus received 80.6% of the overall royalties and Olsen

17.7%.

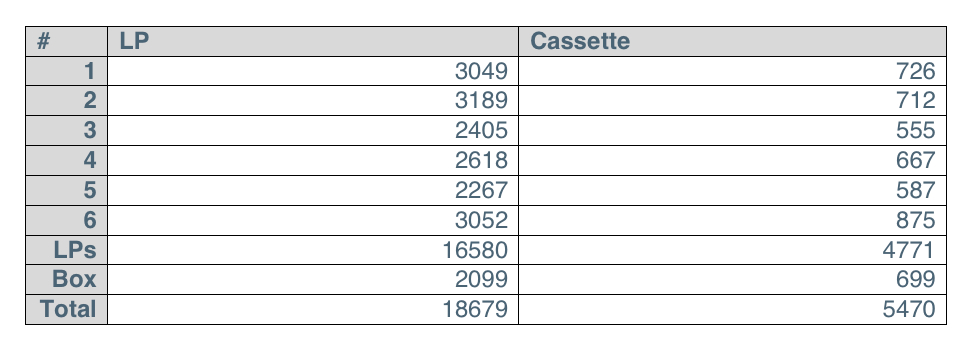

The total reported units sold through March 1981 are:

These figures indicate that without question MIWI was a huge

commercial

success in its first five years, indeed a complete rarity in the world

of both recordings of Middle Eastern music and scholarly

ethnomusicology or folk or documentary recordings. Tangent’s

statements report total royalty payments through March 1981 of

£4,418.87 to Jean Jenkins and £988.08 to Olsen.

Such figures are highly atypical for that time of the level of

royalties that were personally paid to collectors and publishers of

“ethnic” or “folk” music

documents published in an academic fashion. And they only represent the

worth of the albums during their first five years, indeed precisely to

the moment when Tangent became Topic, and when My Life in the Bush of

Ghosts appeared and could potentially have contributed

regular

secondary royalties.

Follow the money

Despite the lucrative royalties paid from sales of MIWI in its first

five years, there is no indication that any of the performers recorded

by Jenkins or Olsen shared in their earnings. Yes, this was typical

practice for many recordist-collectors at the time, but given the

commercial scale of the project it is still surprising that royalty

compensation for artists is nowhere considered. Indeed, the matter is

only clarified obliquely, in a February 17, 1976 letter from Jean

Jenkins to Salman Shukur, a performer on the Lutes

volume (LP 3) of MIWI.

Jenkins wrote:

Obviously an anthology of this kind rules out the possibility of royalties being paid to individual musicians, because the sales do not normally approach the point where this is commercially feasible…If I were to share with you royalties receivable on your 3 1/2 minutes, in the light of expected sales it is unlikely that you would get more than £15 to £20, but as I am sure you would find the money useful, I am prepared to offer you £50 in full and final settlement for the use of your 3 1/2 minute recording, as under no circumstances will Tangent Records be liable for any payment whatsoever to individual musicians. They also must be indemnified against any possible claim for the use of copyright material – which in this case is highly unlikely anyway.

Jenkins made just over £4418 in royalties in

the first five

years of the MIWI

recordings. Taking that five-year figure to a

per-minute basis (£4418 -/- 250 minutes total =

£17.6/minute x 3.5 minutes ) Mr. Shukur would have made about

£62 in those first five years after publication. But

exactness of per minute compensation is not the point here. The point

is that the musician is treated as a nuisance, an unruly child whose

ownership or compensation concerns are dismissed by rude scolding

(“Obviously…,” If I were to

share…” ) and patronizing language (“as

I am sure you would find the money useful…”).

Notice, too, the final sentence; how ironic given what happened to

copyright material with MLBG.

In a final paragraph to the letter Jenkins reminds Shukur that he is to

come to London and perform briefly at a private showing and at the

opening of the Music in the World of Islam exhibit. She tells him that

the curator of the museum will be writing and will offer hospitality

and a fee for his two performances. The same brusque tone continues:

“As we are not a wealthy institution, but only a poor museum,

we will do the best we can for you – but please

don’t expect too much (our oil is not flowing yet). However,

you will be heard by a number of people who may be both useful and

important to you – the same goes for the record, you realize.

Incidentally, Tangent have agreed to send you half a dozen free copies

of the record when it is out.”

One can also find in the archive of Jenkins’ correspondence

some letters indicating another dimension of the possible worth of this

project. On June 2, 1981, the UK Mechanical Copyright Protection

Society Ltd.'s Licensing Department responded to inquiry from Lost Ark

Productions concerning use of up to five minutes of music from the Music in the World

of Islam LPs for the Steven Spielberg film Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The proposed fee was

£4000. On June 10, Lost Ark Productions declined the proposed

contract, indicating

that “the asking price was somewhat steep” (Davage

1981, Carr 1981).

Other items of Jenkins’ correspondence also make clear that

she was in no way naïve about the commercial potentials of

recorded music and about the licensing of it for secondary markets. For

example, Jenkins received a November 23, 1981 letter from Anthony

McNicoll, an archeologist at the University of Sydney. McNicoll reminds

her of meeting in Afghanistan in 1976, and tells her that he is

co-directing a dig in Jordan, to be the subject of a TV program on

Australian ABC TV. He requests permission to use “a few short

bursts” from the MIWI

records. “I realize that

there may be problems which prevent you from giving permission, but if

it is at all possible, I would be most grateful. If we can use them,

please let me know what credit(s) should be given.”

Jenkins wrote back promptly, on December 8, 1981:

In so far as using music from my Islam records, I can give you permission to do so under the following conditions: Credits: Recordings Jean Jenkins and Tangent Records. ABC undoubtedly has a standard fee per second of music used. I cannot tell you precisely what it will be, since I know that it varies between the UK, USA, Germany, New Zealand, Canada, etc. (in all of which some of my music has been used on television films). I would expect the money for the exact timing to be sent directly by bank transfer to my account at Lloyds Bank, Cox’s and King’s Branch, 6 Pall Mall, London SW1. Account number 2653486. Alternately a cheque could be sent, but I think you will find that all television companies prefer the direct bank to bank method.

Here a number of points need to be underscored, aside

from

Jenkins’ reference to “my Islam record,”

in stark contrast to Olsen’s “our Islam

album” in his previously cited letter to Michael Steyn.

Jenkins was well aware of the licensing and payment standards for

secondary uses of recorded material. She doesn’t ask what

tracks, how much time, what context of use, or anything else indicating

concern with stewardship or advocacy for those recorded. She assumes

that the material chosen will be her recordings only. She asks only for

credit for herself and Tangent; she does not ask for any credit for the

recorded performers. She does not ask for credit for the record series,

or the specific LPs. She makes clear that she has made similar business

deals with other TV companies. And in that context refers to the use of

field recording excerpts as “my music” making clear

her proprietary sense of ownership at all levels.

Collaboration and

the business of MIWI

The background to the Jean Jenkins-Poul Rovsing Olsen collaboration for

Music in the World

of Islam dates to a collegial friendship that

developed from the 1960s. In early letters found among

Olsen’s correspondence in the Danish National Archives, we

read how Jenkins, already a folk music recording entrepreneur, took on

the mentoring role, counseling Olsen about how to be an independent

folk music collector outside the academic circuit at the moment of his

transition from employment at the Ministry of Education to the DFS. In

Jenkins’ 1963 and 1964 letters, written either by hand or on

Horniman Museum stationary, she encourages Olsen to bring recordings to

the UK for sale and indicates that this is a good method for financing

travel and research, an alternative to the way Olsen was financing his

early recording trips by writing critical commentary for newspapers. In

a letter dated June 16, (probably 1967), she wrote:

The BBC is interested in the tapes. They pay between 1.11 and 1.10 per minute, so you can pay all the costs of such a trip that way, having the newspaper money for other purposes.

That Jenkins was well in touch with the financial

potentials of music

recording and secondary licensing for commercial purposes is clear in

these and other documents. In keeping with the practice of the time,

she assumed, and advised Olsen that collected recordings were the

exclusive property of the collector, and that her rights as recordist

and physical owner of original field tapes also included all and any

rights to reproduce, circulate, sell, and profit from such recordings,

without prior or sustained contract with, the expressed consent of, or

obligation of compensation to those musicians whose voices or sounds

were recorded.

When she developed the MIWI

project ten years later, Jenkins wrote to

Olsen on March 12, 1975 about her decision on a structure for the LPs,

and his participation in royalty shares:

The records I have decided to do on a typological basis. That is, I am thinking along the lines of ‘Flutes of the Islamic World,’ ‘Drums of the Islamic World,’ ‘Reed Instruments of the Islamic World,’ and two on stringed instruments, one of which may be called ‘Lutes of the Islamic World.’ Obviously the reason for this approach is that it is quite impossible for us to include records of music from each locality or country, and we do not wish any area to feel ‘left out in the cold.’ This means, of course, that you and I will have to combine our recordings, and we will share the royalties on a pro Rata basis...

While Olsen accepted the plan, correspondence makes it clear that he was unclear if not uneasy about his academic position in the project and his vague business relationship with Jenkins and Tangent. On December 3, 1975, he wrote to Jenkins:

We have to find out about my position in the whole business. No need to tell me that I do not act as a kind of assistant to you – I know that this is not your idea. But then it would certainly be reasonable, if we found a subject, where I held the responsibility so that the last word would be mine. Say the seminar.

Olsen is referring to the academic seminar planned to go with the MIWI exhibit and book/LP publications. He wanted something of his own in the enterprise. Aside from his important scholarly bibliography for the book, Olsen was to be given the lead role in this more academic colloquium, but later he was cut out of the planning, and then the event was cancelled, Olsen informed in a curt letter from the World of Islam Festival’s Performing Arts organizer (Ross 1976). In the following six months, Olsen became more agitated by the lack of contract and clarity in ownership and royalties and the diminished scholarly dimension of the project. He wrote to Tangent’s Michael Steyn on official DFS letterhead on June 23, 1976, requesting an accounting on the share participation:

I know you are busy and that you are doing important and interesting things. But when you find the time for it, please do not forget to send me the note about the “minutage” for the six Islamic records.

Steyn answered on August 3,1976:

I must apologise for the very long delay in writing to you – I cannot believe that it is August already. The whole year seems to have been dominated by my involvement with the World of Islam Festival, in addition to which I have moved house. However, you will be pleased to know that the records have been quite successful, with sales now standing at approximately 1500 of each of the six. Cassettes are also out, but they were unfortunately rather late. I have not yet had time to complete the ‘minutage’ but I really do hope that I will be able to send you all information concerning percentages and timings etc. in the very near future.” He signed the letter: “ Hoping that your patience will last a little longer, and that you are flourishing.

A letter of assurance from Jenkins to Olsen follows, on August 12, 1976:

…Our friend Michael Steyn is still alive but frantically busy and to a large extent this business is concerned with selling our records and I think that you would prefer him to be busy about this rather than to write letters! I have not got a contract either but I know that he has finished selling the first 1,500 of each record and that he has re-pressed another 1,000 of each and that these are almost finished as well, so that although his production costs have been very high at least the sales seem to be going equally well.

Three months later Jenkins again wrote to Olsen, on November 19, 1976:

I rang Michael and he told me that at long last he had managed to complete the minutes on each record which belong to each of us, together with a statement of accounts up to the end of September, and he also tells me that he sent you a cheque for £500. I do hope that this has arrived safely. Of course I know that at today’s rate of the £ this is probably chicken-feed to any Dane but perhaps it would be a good idea to come over here and spend it in England…

From 1977 the correspondence between Jenkins and Olsen

diminishes

quickly, then ceases, after many years of frequent and collegial

exchange. Friends acknowledged that by 1978 the two had gone in very

different directions. The last letters Jenkins wrote to Olsen indicate

distress that he was no longer in touch.

Jenkins had other reasons to be distressed. Her employment was

terminated at the Horniman Museum and the separation was acrimonious,

leaving her vulnerable, angry and, by all accounts, quite bitter. She

took consulting and curation work where she could get it, and did not

do another major exhibit until 1983, in Scotland. After her death in

1990, Jenkins’ collection of instruments, photographs,

recordings, and documents was donated to the National Museum of

Scotland by Anne Zeeberg, her long-time Danish friend, executor, and

estate beneficiary.

Olsen, on the other hand, was, from 1977, increasingly aligned more

with scholarship than collecting, becoming a major presence in

professional ethnomusicology, his presidency linked to the

transformation of the International Folk Music Council to the

International Council for Traditional Music. He was also increasingly

involved in contemporary art music composition. In the last five years

of his life he was an internationally visible and well-acknowledged

cosmopolitan in both the intellectual and musical senses. At the same

time he too had disappointments, particularly around the lack of

academic acknowledgement in the form of a regularized professorial

position.

It is evident that Jenkins and Olsen fell out in the end, opting for

different academic and personal styles of scholarly presence. As Anne

Zeeberg put it: “She was kind of a sharp person who was

either very good friends with people – or not good

friends.” This might be the reason why Jenkins and Olsen did

not confer about MLBG

or take any mutual action in response. Jenkins,

of course, certainly had a serious professional and personal stake in

this matter too given the inflammatory use of her recording of Quranic

recitation on MLBG, and the protest and ultimately the self-censorship

that resulted (the subject of the companion piece to this article, Feld

2007, 2011).

Back to the radio

tapes…

As Louise Lerche-Lerchenborg tried to help us work out both the

chronology of who knew and did what and when, we discovered that she

had a cassette copy of a program with journalist Ole Reitov presenting My Life in the

Bush of Ghosts. It was broadcast by Danish Radio on P3,

the rock channel, likely on a program called Rock News, in March 1986.

The first portion of the tape of thirteen minutes is an interview with

Olsen and the second portion an interview with Brian Eno. The Olsen

interview is in Danish and edited from the taped conversation made in

August 1981. The Brian Eno portion, in English, was recorded in

Stockholm on November 4, 1985. Here is Kirkegaard’s annotated

translation of the Olsen interview, with commentary in brackets

indicating paralinguistic features that would be evident to Danish

listeners.

PRO (after listening to “Abu Zeluf”): What she is singing is a classical Arab form of poetry, which I believe [it is audible that he is looking down, possibly to his notes] is called “Abu Zeluf” [he in fact says ‘Zaluf’]. It is a kind of poetry sung by Arabs, women and men, when they meet and socialise for a whole evening, when they improvise poems for each other, play for each other and sing for each other. Originally a drum should have accompanied the singing. There was no drum at that event in Munir’s – ehhh – at Munir’s office, so that is why there is no drum in the recording. And apart from that, I was so struck by the fantastic GO [a typical Danish use of the English word from the time indicating power and drive] that dominates her singing, so in fact I do not think that the drum is lacking.

OR: But drums were added later…Apparently others – for instance Brian Eno – felt that her song could be elaborated. What do you think of this idea?

PRO: [After listening to “Regiment” on MLBG; very heavy breathing] Yeees, Ehhh – In a way I do think – [pause, sigh] – I perhaps have an ambivalent attitude here [big stress]. On the one hand I think that really people should be allowed do what they want [big stress]. If you are inspired by a piece of music to create something else then it is - ehhhh – why shouldn’t you do that [extremely powerful and emotional stress]. Something new comes out of it and it means that what she did in fact had a life-giving power. This has been done many times and should you not do that [again a huge stress]. The only concern I have on this is – and this is generally speaking – that in fact I would be a bit sad, if the whole world gradually would just become some kind of grand cocktail. If all the different forms of local style – let’s say dialects and diverse musical languages – would all constitute a higher or lower kind of unity. It is wonderful that there are all these different experiences of what music is [stress], what music means to people and how music can sound - the different ideals. But – ehhh – hopefully it is only to be pessimistic to think that it should come that far.

OR: Do you think that this kind of adaptation of an original thing can possibly make another kind of audience listen to the original recordings?

PRO: [Sigh] I don’t know [sigh]. One can only hope. You have to do that…. [sigh]. It will depend on how much significance of the original recording has been preserved in the adaptation – ehhh – in this case you could think so – there is after all so much of her typical Lebanese [sigh, sigh, sigh] mountain singing – ehhh, ehhh – idiom left here. So if you are taken by the adaptation, then maybe you would also like to listen to the original. I hope so! [in firm voice]

When put on the spot about the

“Regiment”

track’s use of his recording of Dunya Yunis singing

“Abu Zeluf,” Olsen was circumspect and reserved.

The key word he used to describe his response was

“ambivalent.” But as we listened together to this

portion of the interview Louise Lerche-Lerchenborg pointed out that

Olsen’s word choice was diplomatic at best.

According to Lerche-Lerchenborg, Olsen traveled to London five times in

1975-6 to work with Jenkins on the editing of the recordings. At that

time he communicated with Dunya Yunis’ family through Munir

Bashir. He asked permission to publish the “Abu Zeluf

“song and told them that the recording would only be

published on MIWI

and also used for a scholarly broadcast.

Juxtaposed with the Olsen interview is a later conversation between Ole

Reitov and Brian Eno, recorded in Stockholm on November 4, 1985. It is

also worth presenting in its entirely because of the way it reveals the

aesthetic ideology that grounds Eno’s practice of

incorporation and fusion. Key discourse frames are underlined.

BE: I think that there’s a big danger with just being attracted to the exotic you know; one so often hears things that have, that are pop records with a bit of African drumming, or, it just becomes a kind of gloss on the music, or the fashion for having a gospel choir singing your backup vocals, that kind of thing. And I’m always so nervous of doing something like that, I never want to do that because I think, I think its kind of an insult to the music that you’re borrowing to do that with. Because you know like I know someone recently who’s making a record – I shall not name him—and he knew I was interested in gospel music and he’s a rich pop star and he said to me ‘I want the best gospel group to sing backup vocals on my song, tell me which is the best gospel choir’ and I said ‘I’m not going to tell you, I’m not going to tell you who that is because I don’t think that’s a good idea to use them as your backup vocalists.’ So yeah, I’m not so keen on the fusion idea unless of course it’s a genuine –, you know there are genuine fusions as well which aren’t so intellectual as that. Because really what that is that style of fusion is, it’s an intellectual notion that yes, I’m just going to put these two cultures together, it will be terribly exciting and everyone will think I’m really liberal for doing it.

OR: (inaudible word)

BE: Yes, there’s some fusions that are very interesting like the music of Bo Diddley was a good fusion of Western and African popular musics. Then some of the rappers have been good fusion merchants as well. But those seem a little bit more innocent than this thing you get from slightly intelligent clever English musicians who think that they would like to put a few exotic ingredients into their song.

OR: In your own case, for instance, My Life in Bush of Ghosts, I was always interested in that; how, when did you come across The Human Voice album?

BE: I can’t really remember; I had that record, I bought that whole series of records when they came out, because I love Arabic music, any of it, I guess I listen to it more than any other culture music apart from my own, um, I listen to a lot of Arabic music, and I love that album in particular, I thought that was a beautiful record.

OR: Did you ever have sort of second thoughts about the use of some music done by some people you’ll never meet and you’ll never know, whether they would like it or not, or whether it would be quite natural for them?

BE: Well I didn’t think I …what I thought about it was that I must at least make it clear who the people were and which records I had taken it from, which I did on the cover of the album because I thought it would be, it would be very rude just to take the music and not, um, give any credit for it. But I thought about it, like, I thought, if somebody did this to my music what would I think, you know if some Arabic person took a couple of lines of one of my songs and put them in an Arabic pop song, and I thought, I’d be absolutely thrilled (laughter), I would! It would be like a wonderful thing to happen. And I couldn’t honestly conceive of any of those people making an objection. Now of course all these people were contacted where it was possible. We couldn’t contact Dunya Yusin (sic) but we contacted the record company, Tangent Records, and asked them if they thought it was ok to use it so we didn’t do it completely without asking permission, but sometimes it wasn’t possible to find people. But this is, it’s tricky, I know it’s a tricky area, morally, because, um, you know, how do you…of course, we earn money from that record.

OR: (inaudible sentence)

BE: Well, that’s what I thought, I thought I don’t think this can do the people any harm because mentioning those records, I mean, I’ve met so many people who said, ‘oh yeah, after that record I bought The Human Voice in the World of Islam and, and for many people that opened up a door to the music of another culture.”

After their 1985 conversation, and its radio broadcast in Denmark in 1986, Eno wrote to Reitov from London, a handwritten and undated letter in early 1987.

Do you think it would ever be possible for me to find a copy of the complete Dunya Yusin (sic) tape from the musicologist? Also, would it ever be possible for her to hear what I did with her singing? Or do you think her father would want to shoot me?

Reitov responded about four months later, in late Spring 1987 anticipating Eno’s appearance in Copenhagen for his August moonlight concert titled “An Opal Evening.” He wrote:

It’s been years since our short meeting in that cold hotel room in Stockholm talking about the famous Dunya Yusin (sic) tapes. Well, the interest of the tapes have never left me. But it has been a little difficult. The complete tapes exist and are stored – a bit too well – in the Danish Archives of Folklore. To get a copy is impossible, but I have had correspondence and personally met Mrs. Louise Lerche-Lerchenborg, who is now the copyright holder of the tapes. Mrs. Lerchenborg was married to the composer/musicologist Poul Rovsing Olsen who recorded Dunya Yusin (sic). And when he died some years ago his wife took over the rights. But physically the tapes are with the archive. Mrs. Lerchenborg, who is very active promoting contemporary classical music, has agreed to opening up the archive so that you can listen to the tapes if you are interested. Unfortunately the rules for copying are extremely hard. So you won’t be able to get a copy. The problem is that there unfortunately are some hard feelings about the dealing of rights in connection with ‘My Life…’ Tangent Records claim that they were only paid 100 Pound Sterling, half of which went to Denmark. Mrs. Lerchenborg and her husband felt that Dunya Yusin (sic) –not being asked- should have had some compensation or say. I’m mentioning this so that you understand the problems I’ve faced when I suggested that the tapes might be of further interest than to the shelves of the archive. I suppose that Tangent simply did a very bad deal and that the musicologist never realized that his original contract could be used that way. Anyway, that is history now…

Radio Journalism,

another Bush of Ghosts

The 1981 and 1985 interviews, the 1986 radio broadcasts, and the 1987

letters reveal Danish Radio and Ole Reitov’s critical

position in exposing the depths of the “Abu

Zeluf”/”Regiment” drama. Reitov was

employed full time at Danish Radio, and in charge of world music at the

time of MLBG’s

appearance in 1981. A music journalist with

Africa and India interests, his programs were broadcast on P3, the rock

station. Speaking to Ole Reitov in recent years and benefiting from his

efforts to help us track audio and written materials related to this

case, we became more critically aware of how Danish rock radio and

world music journalism was central to animating this story’s

contacts and conflicts.

First, consider Reitov’s role in presenting the MLBG LP to

Olsen, and soliciting his on-the spot reactions. Olsen’s

response reveals how unaware and unprepared researchers once were about

scholarly complicity in musical commoditization, about their inability

to “protect” recordings and those recorded, about

new regimes of copyright, circulation, and valuation.

Second, focus on Reitov’s role in soliciting serious

reflection from Brian Eno. If “ambivalence” was a

key word in Olsen’s response, it was equally a key frame for

Eno’s discourse. Notice how Eno foregrounds aesthetics and

then comes around to ethics and morality and finance, each phrasing

revealing more ambivalence. But ultimately it is Eno, not Olsen, who

brings up the anxiety that “insult” to the

“borrowed” music might not be mitigated or balanced

by one’s “love” for it, and the

recognition that making money from the use of other peoples voices and

recordings is “morally”

“tricky.”

The 1987 letter exchange is even more poignant in this regard. Eno

asked Reitov to be his advocate with DFS and Louise Lerche-Lerchenborg

toward getting access to Olsen’s complete Dunya Yunis

recordings. And in the process of trying to do that, Reitov was exposed

to the lingering bitterness over the original split. From there it

became Reitov’s responsibility, clearly discharged, to

concretely present to Eno the specific consequences of his actions.

To grasp the significance of Reitov’s position here, imagine

how different this story would be if Eno had made direct contact with

Olsen and DFS at the origin and the follow-up points in this chronology

(1980-1982). Imagine how things might have unfolded if Eno met Olsen to

talk about his love of Arabic music, his ideas of avant-garde culture

grafting, his belief that using excerpts from “Abu

Zeluf” would bring only respect and no harm to its original

singer. Imagine the conversation if it was Eno telling Olsen that he

was aware of the dangers of “insult,” of the

“morally” “tricky” side of

“earning money” from a recording. And imagine Olsen

reflecting on the money he earned and/or the money Dunya Yunis

didn’t earn from this recording, before and after MLBG.

Imagine Olsen telling Eno about his anxieties that avant-garde rock

experiments could topple into his nightmare of a global pop

“cocktail.”

Would the final result of that imaginary conversation be Olsen shutting

the door at Tangent, meaning that Eno and Byrne would have been blocked

from “borrowing” “Abu Zeluf”?

Would “Regiment” and “The

Carrier” now not exist? Would music history look back at

Olsen and say his protectionism amounted to censorship and copyright

bullying? Or would Olsen and Eno, as contemporary composers, as

internationalists, as Arabic music lovers, as anxious globalists, have

found some kind of aesthetic and humanist common ground, leading to a

EG-Tangent arrangement that could include informed consent and proper

financial compensation for Dunya Yunis, insuring that, among other

gestures of respect, her name was spelled correctly in MLBG’s

liner notes?

The Archive as

Contact Zone

To juxtapose the role of radio with the other critical institution in

the story, Annemette Kirkegaard animated a conversation (in Danish) in

April 2006 at the Dansk Folkemindesamling with Sven Nielsen (SN), a

folklorist who worked there with Olsen for many years, and Jens Henrik

Koudal, (JHK), a musicologist who continued Olsen’s work

there in the late 1980s. In the edited transcript that follows, she

started by asking about Olsen’s awareness of MLBG.

SN: Oh, Poul indeed knew. It must have been during his last year. And we talked about it because it was something other – something very special. But he shrugged his shoulders and said that he couldn’t bother to spend time on it.

AK: DFS initially owned the rights for this recording. What is/was the normal procedure in such cases?

SN: Well, there are both the rights of the informants and those of the collector to be respected. Our custom is that we don’t demand money if the recordings are used for study and research, people can come and listen. But if the recording is broadcast, a fee must be paid [by the radio] to the ‘informant’ [i.e., the person(s) recorded]. It has always been like this; we have always believed that the DFS held the rights as such.

Fully aware that DFS had a tradition of legal contracts with “informants” from the late 1950s, including payment of 100 Danish kroner for broadcast or publication, Kirkegaard continued:

AK: Did Poul actually pay his “informants” [those recorded] if he broadcasted their music?

SN: No, I don’t think so.

AK: Were there different rules for non-Danish “informants?”

SN: No, they are identical.

AK: We know that there was a program on the radio in which he played the “Abu Zeluf” track.

SN: He might have considered this part of his personal research, and accordingly for his own use. I do not believe the radio paid a fee.

AK: Then what about the Music in the World of Islam LP release; that is some kind of semi-commercial release.

SN: I don’t remember anything of how this came about, and I simply do not believe that Poul involved others in this matter. Nobody at DFS was involved. The overriding condition is that he did not know about My Life in the Bush of Ghosts in advance, otherwise he would very likely have tried to interfere, especially because he had promised not to use it commercially.

AK: Morten Levy has it that Poul would not have approved of ”Regiment” and ”The Carrier”? Do you agree?

SN: I do not think so either. He simply stated that position at one time, but said that he did not want to waste time on it.

AK: Going back to what you say about rights. I have seen the meticulous contracts made with Danish informants in the files. Isn’t it a little strange that there are no such documents for the “foreign” recordings? Was there a different attitude towards people from “out there”?

JHK: Or is it (addressing SN) as it was in the case of Jørn Piø, [a former archivist at DFS] that your own research and contracts for all that was not something of concern to others?

SN: He definitely saw such things as a matter of his own research and his own materials…

JHK: When Piø published books commercially (which he often did) then it was considered that it was the archivist himself (the scholar) who made appointments and contractual arrangements outside the archive.

SN: The difference is that if it is an employee, an archivist, who releases material, then he is responsible for looking after these things and he has the responsibility towards the informant. But of course there have been great differences between how this has worked with books or texts and sound recordings.

AK: So, it seems Poul had taken on himself this responsibility to get permission to publish the “Abu Zeluf” track on The Human Voice in the World of Islam, and that this also was the reason why he became so furious?

SN: Well yes, because whether or not he would accept what happened with MLBG he did have that responsibility – because he was the person to publish the material.

AK: How is it with the master tapes and the original recordings here? How are they reproduced – and transmitted? How would this have taken place for instance, getting a master from the original recording of “Abu Zeluf” to the publisher of The Human Voice in the World of Islam?

SN: The originals are always kept here; a copy must have been sent.

HK: The original tapes never leave the building; (addressing SN) could Jens have made a copy?

AK: Who is Jens?

HK: Jens Bager, the sound technician at that time, he is still alive. He probably made a master tape from the original; if it ever came back we do not know; it is unlikely that it was returned. The normal procedure at DFS in relation to release of sound recordings is that the original tapes remain downstairs. We have always been very cautious about letting anything leave there. The original field tapes stay there and the link between them and any outside record production is what we call the master tape. There must have been a master tape on which the items chosen for publication would have been copied and sequenced.

Jens Bager, who frequently assisted Olsen and other

staff members in

this practice, confirmed the procedure when contacted later by AK, but

does not remember the exact case of “Abu Zeluf.” We

cannot say for sure, but must assume, with Nielsen and Koudal, that

DFS’s master tape was taken by Olsen to Tangent Records for

the production of MIWI.

Interestingly, the DFS position on rights, access, and responsibility

outlined by Nielsen and Koudal is contradicted in a 1989 DFS-published

collections document, Extra-European Music in Danish Folklore Archives:

A Catalog, prepared by Jane Mink Rossen and dedicated to Olsen. The

final lines to the catalog’s introduction read:

Rights to the material belong to the individual collectors. To obtain copies or to publish material from the collections, permission from the collector is required. The recordings are, however, available for listening purposes at the Danish Folklore Archives, by appointment only (Rossen 1989:11).

This statement, while not “official”

policy was

likely the de facto understanding among those at DFS working on

“Extra-European” musics in the 1960s and 70s, and

this explains some of the discrepancy between Olsen’s own

practice with MIWI and the standard DFS broadcast and publication

practice for Danish collections.

But to return to the conversation, the final topic turned to legal

challenges experienced by DFS concerning ownership and the rights of

collectors. Nielsen and Koudal explained that DFS consulted the State

Attorney in cases that involved a conflict of position on rights, and

that from those consultations came to the position that, in

Nielsen’s words: “what was decisive was who had

initially paid for the procurement of the material.”

The conversation closed like this:

JHK: It is all very complicated – it is about morals, too – not just law!

AK: Yes, but still it is remarkable with Poul since he was also a professional lawyer.

JHK: He probably did not –could not– foresee what this could result in. We can now see that it became a big business, but that was hardly realised by Poul at the beginning of the 1980s, he did not imagine that it would ever go this far. But the State attorney –and we work from this statement – did decide that the rights belong to “those who paid for the recordings” – it didn’t go to trial, but still we have some guidance here.

SN: Of course you can still make special, written agreements to the contrary, or on different grounds. And the rights of the informants are still quite unclear. I almost had the impression from the state attorney that it was doubtful if the informants had in fact any lawful rights whatsoever (copyright) as their music or songs were not seen within the work concept.”.

How Far Can

“It “Go? On the Matter of Legalities…

Indeed, Olsen likely did not imagine how far the business of

“ethnic” music might go. But had he lived and later

decided to take up some kind of legal intervention with Tangent and

World of Islam Trust over the use of the “Abu

Zeluf” recording, he would actually have been on very solid

ground, as would Jenkins if she similarly pursued the matter legally

regarding her recording of “Recitation of Verses.”

A simple inspection of the undated draft contract held in

Jenkins’ and Olsen’s files makes clear the critical

clauses for such a case, excerpted below:

(1) "It is to be understood that the music contained in the recordings

issued by us (as distinct from the recordings themselves) shall be

considered traditional and non-copyright."

(2) "Tangent Records will apportion revenue received from film or

television use as follows: where such use is directly initiated by your

own involvement, 60% will be paid to you and/or Poul Rovsing Olsen;

where such use is not directly initiated by you, 50% will be payable to

you and/or Poul Rovsing Olsen."

(3) "Tangent will be given first refusal should you wish to publish any

recordings assigned to Tangent under this agreement with any other

company or institution or publisher for different uses..."

(4) "Tangent may re-assign its rights under this agreement to other

companies or institutions or publishers subject to your written

approval.”

Clauses 1-3 establish that the two recordists (as opposed to those

recorded) are owners and legal partners, and they also establish the

principles of license and of rights and compensation for republication.

But clause 4 establishes the explicit grounds on which Jenkins and

Olsen could claim contractual violation, namely, that Tangent did not

consult them for written approval to grant license to EG Records for

use of “Abu Zeluf” and “Recitation of

Verses“ on MLBG.

Entangled

Complicities

While dramatic, the many layers of professional and personal complicity

in this story are not unique and they are by no means something of the

past. Things like this have been and are being experienced by many

researchers, in many countries. Simple villain vs. victim narratives

are not the name of the game here. Rather, what we have been describing